REVIEW: Didion's Artist Sketchbook of Her Travels in the South and West

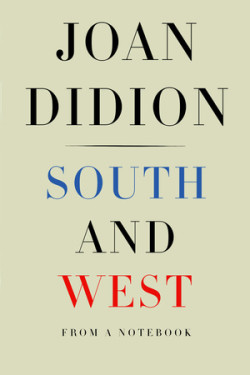

/South and West: From a Notebook by Joan Didion

Knopf, 160 pp

Joan Didion’s South and West: From a Notebook gathers up notes Didion took during a June 1970 road trip around the American South. The trip came about when, not sure of her next writing project, Didion asked her editors at Life to send her south. They did, and Didion and her husband, writer John Gregory Dunne, rented a car in New Orleans and drove through Mississippi and Alabama.

Didion’s notes describe the standard stuff of southern road trips: dusty towns, gas stations, motel pools, Confederate flags, bourbon, kudzu, swamps and snakes. In fact, lots of snakes—water moccasins, king snakes, pit vipers, cottonmouths, black snakes and even a couple of lethargic boas, caged up at a muddy reptile park.

The West gets covered in a dozen pages written in 1976 while Didion was reporting on Patty Hearst’s armed robbery trial for Rolling Stone. Didion never published the articles she’d planned on the South or on Hearst but judging by what she set down in South and West she is a sharp-eyed note taker, a skill she’s been polishing for most of her writing life.

Fifty years ago (take a minute to let that sink in and think how lucky we are to have lived so long with this writer) Didion published a short essay “On Keeping a Notebook.” The piece appeared in Holiday, a magazine for literary-minded travelers with a liking for jotting things down. “On Keeping a Notebook” still turns up as required reading in college writing classes, but Didion warned her readers not to expect too much from their notebooks.

“I sometimes delude myself about why I keep a notebook, imagine that some thrifty virtue derives from preserving everything observed. See enough and write it down, I tell myself, and then some morning when the world seems drained of wonder, some day when I am only going through the motions of doing what I am supposed to do, which is write—on that bankrupt morning I will simply open my notebook and there it will all be, a forgotten account with accumulated interest, paid passage back to the world out there.”

Open a notebook on that bankrupt morning, though, and all you’re likely to find is a glimpse of your old self coming back at you carrying “bits of the mind's string too short to use, an indiscriminate and erratic assemblage with meaning only for its maker.”

It’s hard to read Didion’s South and West without picking up an echo of her old advice. Didion says she wasn’t sure why she wanted to write about the South. “I had only some dim and unformed sense, a sense which struck me now and then, and which I could not explain coherently, that for some years the South and particularly the Gulf Coast had been for America what people were still saying California was, and what California seemed to me not to be: the future, the secret source of malevolent and benevolent energy, the psychic center.”

But how to find that psychic center? She skips the Miss Mississippi Hospitality Contest (probably a good thing if you’re tired of seeing the South as an endless loop of Honey Boo Boo) and misses the interviews she scheduled at a College of Cosmetology. She talks to a handful of white southerners, picks up a whiff of death and decay, eavesdrops on conversations in an elevator and a laundromat, spends a day at a radio broadcasters’ convention, has a drink with Walker Percy, tries to find Faulkner’s grave, and looks over the Gulf Coast towns that Hurricane Camille battered in 1969.

Of course, the Civil Rights Movement gnaws along the edges of Didion’s notes. It’s the real reason behind her trip, the prompt for her questions, and the implicit context for much of what she sees. Sheriff Bull Connor and Governor George Wallace are on her mind. Her route skirts along the region’s recent murders: the school girls killed in Birmingham, Alabama, in 1963; the Civil Rights workers in Philadelphia, Mississippi, in 1964; and the students at Jackson State in May 1970, just weeks before Didion headed south.

Didion admits she never quite got the southerners she met. She calls a friend in the Berkeley English Department. He can’t think of a single faculty member she could call at any college anywhere in Mississippi. Maybe she could call Miss Eudora Welty in Jackson, he says. His sad comment adds to Didion’ sense that the “isolation of these people from the currents of American life in 1970 was startling and bewildering to behold.” Isolated from Didion’s bi-coastal American life, that is. “I never wrote the piece,” she adds, setting the article aside as another of the decade’s stories that refused to come together.

So what are we to make of South and West in our own new year of scrambled stories? Didion described the malaise of the late 1960s in the memorable essay that opened The White Album. Somewhere around 1968, we had lost track of the plot she said. She had a mind full of images that did not fit into any of the narratives she knew. So maybe we read South and West as a report from a moment of cultural impasse.

Didion’s storied writer’s life also gives these notes a special interest. Think of them as something like an artist’s sketchbook—a chance to watch Didion at work. Some of the material turns up in her novels and in her reports on life and politics. But in many ways, it’s her failure to make sense of the South she saw in June 1970 that makes this little book worth reading: that failure helps us see why her writing on California (and the west) is so good.

California is the territory she knows, a place whose myths and deceptions weave through her own long family story. “I am at home in the West,” she writes at the end of the book. “The hills of the coastal ranges look ‘right’ to me, the particular flat expanse of the Central Valley comforts the eye. The place names have the ring of real places to me, I can pronounce the names of the rivers, and recognize the common trees and snakes. I am easy here in a way that I am not easy in other places.”

Easy is not the first word that Didion brings to mind. On edge, maybe. Didion has woven her life along California’s edges and into its fault lines. She knows the snakes, especially the snakes. Her grandfather taught her the code of the West: if you see a rattler, kill it. If you don’t the snake will slither off into the brush, just waiting there to strike the next guy who comes along.

Didion’s readers all have an outline of her life and with it the sources of her insights into its western codes. She was born in Sacramento to parents whose California families stretched back four or five generations. She graduated from Berkeley in 1955, wrote for Vogue and Mademoiselle, covered Charles Manson, hippies and the Black Panthers, and became New Journalism’s voice of the dark heart of sunny California—the golden land of self-sufficient pioneers blind to the history behind their comforts and clueless about the costs of their mistakes.

Reading South and West we catch aglimpse of the cultural tensions of the late 1960s that launched Didion’s career. We also see some of the ways Didion builds her fictional characters out of people she meets. But if readers want to see the Didion who became our brilliant chronicler of loss, in The Year of Magical Thinking and elsewhere, they should pick up “On Keeping a Notebook.”

There’s a clue in that old essay to how Didion’s note-taking skills prepared her for the heartbreaking artistry of her writing on mourning. “Keepers of private notebooks,” she wrote, “are a different breed altogether, lonely and resistant rearrangers of things, anxious malcontents, children afflicted apparently at birth with some presentiment of loss.” It seems she knew all along where she was going.

Ann Fabian writes about American history. She is living in Tokyo but working on book about American natural history.