ESSAY: The Trump and Xi Jinping Era: Finding Support in Music and Words

/Credit: Gage Skidmore

By Jeffrey Wasserstrom

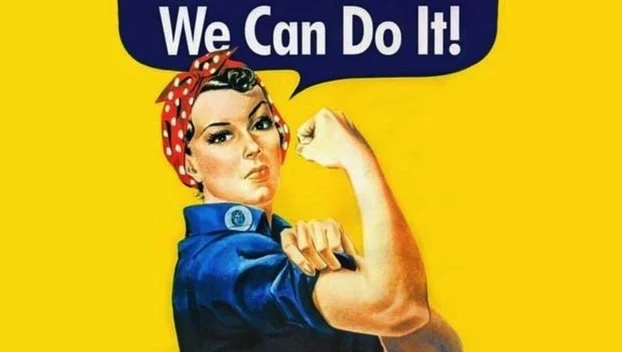

Late in January, with memories of the trauma of Donald Trump’s rise to power and the exhilaration of joining a massive crowd at L.A.’s Women’s March fresh in my mind, I found myself continually listening to two songs. They were both ones I had enjoyed listening to before, but each had suddenly taken on new meanings.

The first song was “Little Victories.” It’s by singer-songwriter J.D. Souther, who is best known to many for the hits he co-authored with members of the Eagles (“Best of My Love,” “New Kid in Town”) and songs of longing and heartache (like “Faithless Love”) that he and Linda Ronstadt—some of whose best tracks he sang harmony on and produced—each recorded.

“Little Victories” isn’t a new song or an explicitly political one, but it felt so fresh and topical in January that whenever I was in my car, I found myself hitting the advance button until I came to it on Souther’s Natural History, a disc I left in the car’s CD player for many days in a row.

The song begins with bleak lines that seemed to speak to Trump’s election: “When I look up/the sky is falling/The signs of warning/clearly drawn.” A key later verse captures the heady sense of solidarity many of us felt at Women’s Marches in cities across America: “Now as we face our uncertain future/Looking on uncharted seas/We see the tear that runs along the curtain/You step right through, you stand with me.” The song closes with a reference to the importance of small successes in difficult times: “Little victories/I know you need one/Little victories of the heart.”

When working at my computer rather than driving, I often found myself searching out a video featuring a performance of a very different song: Abigail Washburn and Wu Fei’s “Banjo Guzheng Pickin’ Girl.” A joint creation of talented players of the two eponymous instruments (a guzheng is an Chinese zither), it’s a bicultural updating of “Banjo Pickin’ Girl,” an old Appalachian song that a globetrotting American group played in China in the 1930s.

I had good reasons to queue up Washburn and Wu’s video late in January. They happen to be friends. And they were scheduled to come to the campus where I teach soon. Wu was scheduled to play the guzheng at UC Irvine’s Lunar New Year festival, with Washburn joining her on stage for a few songs. And they were both going to take part in a roundtable on “Cultural Flows Between China and America” hosted by UCI’s Long U.S.-China Institute that I would moderate.

These weren’t, however, the only things that drew me to the video in late January. Watching the joy the pair took in collaborating also served as a tonic. It dispelled, momentarily, the despair I felt not just about the political situation in the United States, where I live, but also about the political situation in China, the country I write and teach about for a living.

People have had many reasons to feel distressed about the state of the world of late, but part of the equation for me is a sense that both of the countries I care about most are sliding in the wrong direction. They are closing themselves off from rather than opening up to the world. This is, I’ve realized recently, something of a novelty. For most of my adult life—the sole previous exception being the bleak couple of years that followed the June 4th Massacre of 1989—when I have felt that the United States was turning inward, I have been able to take comfort from the fact that China seemed to be doing the opposite, or vice versa.

In the mid-1980s, for example, I worried about America, but was hopeful about China. In the early 2010s, I was distressed by the way that China’s government was tightening the screws on dissent and pulling up the cultural drawbridges, but felt good about many trends on this side of the Pacific. And so on.

But in this time when Trump talks of building walls, while Xi Jinping sings the praises of globalization at Davos but at home revives the tired old trope of tides from the West carrying spiritual pollution into China, I can’t look to Beijing to distract me from worrying about Washington. Nor do I see hopeful signs coming out of D.C. to divert me from lamenting about what is happening on the Chinese mainland.

What does this have to do with Washburn and Wu’s performance of “Banjo Guzheng Pickin’ Girl”? A lot. Their performance is infused with a sense of easy camaraderie between kindred spirits from opposite sides of the globe who revel in being in one another’s company—something that shows through as well in other works they perform, such as a bilingual blending of “The Water is Wide” and a Chinese folk songs about a boatman.

Their music is a welcome antidote to the America First and China First rhetoric coming out of Washington and Beijing, and to our angry age as a whole. I know that their performances can’t solve big problems. The fact that they create their videos, and that they blend their voices and cultures in concerts and sometimes also in classrooms, though, can be latched onto as “little victories” to be treasured in dark times.

With that thought in mind, I have begun to look for other collaborative ventures that seem to go against the tide that I associate most with Trump and Xi, but that can be tied as well to other strongman poster children for angry wall building. I have also begun looking for ways to draw attention to the collaborations I come across that give me hope. I’ve found three very different ones lately, which have little in common except that each is relatively new, or at least relatively new to me, and seems to warrant being more widely known.

One of the discoveries I want to share is WWB-Campus. I’ve been a reader and a fan of the wonderful Words Without Borders website for years. Its mission has been to raise awareness among Anglophone readers of literature written in languages other than English and to encourage curiosity about and openness to the world. Now it has launched a pedagogic venture, made up of old materials repurposed for classroom use and original texts created with students and educators in mind.

The second discovery that I want to spread the word about is PEN Hong Kong. PEN International—a group whose charter begins with a claim that “Literature knows no frontiers” and includes a commitment to furthering the “unhampered transmission of thought within each nation and between all nations”—used to have a branch in Hong Kong, but years ago it disappeared. Now, at a time when there is a concern about many valued things in the city disappearing due to pressures from Beijing, a group of local writers has revived PEN Hong Kong.

In November, I participated in the Hong Kong International Literary Festival, but left to come back to the United States just before the rebooted PEN Hong Kong’s official launch took place toward the end of that event. I’ve been pleased to keep up with its activities from afar since then via its website and am currently enjoying reading the essays, poem, and stories by local authors (e.g., Ilaria Maria Sala, Mishi Saran, and PEN Hong Kong’s president Jason Y. Ng), as well as some local activists (including Umbrella Movement leader Joshua Wong), that will be included in its forthcoming crowd funded book: Hong Kong 20/20: An Anthology by PEN Hong Kong.

The final thing I want to draw attention to is the Columbia Global Reports book series. One thing we need now more than ever is intelligent, accessible, lively writing that is rooted in careful research and solid reasoning and engages with varied issues and parts of the world. This series speaks directly to this need. Its goal is to publish “four to six ambitious works of journalism a year, each on a different underreported story” and rooted in “original on-site reporting around the globe.” The books, all of them short, are intended to provide “new ways to look at and understand the world that can be read in a few hours.” They are ideally suited for busy people who want to have a sense of what is going on in many places.

The first one I read, among the most recent they have published, is Basharat Peer’s A Question of Order: India, Turkey, and the Return of Strongmen. It lived up to each of the stated aims of the series. I’ve moved on now to an earlier work in the series, Atossa Araxia Abrahamian’s The Cosmopolites: The Coming of the Global Citizen, and so far it is doing the same.

Spending time reading the translations and introductions to the literary scene in different places available at WWB-Campus, the contributions to the PEN Hong Kong anthology, and the books in the Columbia Global Reports series won’t keep the sky from falling. But when the “signs of warning” are “clearly drawn,” in an era when we contemplate a more and more “uncertain future,” we need places to turn for inspiration and information. And when I’m not listening to Washburn and Wu combine their instruments and voices or to J.D. Souther singing about the need for “Little Victories,” these are three places I’ve been turning in search of those things.

Jeffrey Wasserstrom is Chancellor’s Professor of History at UC Irvine, the author, most recently, of Eight Juxtapositions: China through Imperfect Analogies from Mark Twain to Manchukuo (Penguin, 2016). He is advising editor on Asia for the Los Angeles Review of Books and a member of the Editorial Board of Dissent magazine.