REVIEW: The Remarkable True-Life Story of the Original Siamese Twins

/Inseparable: The Original Siamese Twins and their Rendezvous with American History by Yunte Huang

Liveright, 416 pp.

By Ann Fabian

Twin boys were born in 1811 on a houseboat in small fishing village about 60 miles west of Bangkok. To the surprise of mother and midwife, the babies were connected by a four-inch piece of cartilage that joined them at the sternum. The twins grew up normal boys, learning to walk, to write, and to swim, peddling duck eggs to help support the family.

Villagers knew them as the “Chinese Twins,” but they caught the eye of a British businessman who saw money to be made by putting their extraordinary body on the display in cities of the west. He enlisted the help of an American ship captain, and the pair launched the boys into history as the “Siamese Twins.” Their great fame came in the 1830s, when big crowds turned out to see “Chang and Eng”—a curiosity, a “freak of nature.”

Chang and Eng made money enough during the decade to buy a farm and settle in North Carolina. They took the last name “Bunker,” married sisters, fathered a score of children, bought and sold slaves, and sided with the South when the country went to war. Two sons enlisted in the North Carolina militia and went off to fight for the Confederacy. The twins’ celebrity lasted through the war and, pressed for cash, they took to the road again in the early 1870s. Travel took its toll; they died in 1874, shy of their 63rd birthday.

Fame outlived the men. We owe them for the adjective that describes all sorts of “Siamese” connections—from conjoined twins to linked water valves. They’ve inspired metaphysicians and medical men, phrenologists, poets, playwrights, novelists and historians.

Yunte Huang’s vivid Inseparable: the Original Siamese Twins and their Rendezvous with American History is an excellent addition to a shelf of books on the lives and cultural afterlives of the Siamese Twins. Huang, professor of English at UC Santa Barbara, has fit the twins into a complex literary history that mirrors the global story of meetings between east and west. He follows them from the smooth rivers of Siam into their tumultuous rendezvous with America. Along the way, Huang offers something of a master class in how to turn notations in a financial ledger into an outline of cultural history.

Huang knows the treacherous racial terrain behind the meetings of facts and fictions in American culture. His bestselling book, Charlie Chan: the Untold Story of the Honorable Detective and his Rendezvous with American History, introduced us to Chang Apana, a real life bullwhip-brandishing Honolulu policeman. Earl Derr Biggers, a Harvard-educated writer, reinvented Apana as an aphorism-spouting detective, and Swedish-born actor Werner Oland made his fortune putting on “yellow-face” and playing a screen version of Charlie Chan.

“Charlie Chan” set up overlapping connections among these men. Chan, real and imagined, led Huang seamlessly from the history of labor and race in Hawaii to stories of white men at Harvard and accounts of Hollywood’s racial politics.

With a small jump we land on Huang’s own story—a young man growing up in rural China, tuning in late-night English language programs on his grandfather’s transistor radio, studying English in a prestigious program at Beijing University. Huang’s parents sent him out of the country, determined to keep him safe as the government crackdown on student demonstrators in Tiananmen Square turned deadly. He landed in Tuscaloosa, Alabama, where he opened a Chinese restaurant. He left Tuscaloosa to earn a PhD in English at SUNY Buffalo, taught for a time at Harvard and now teaches in California.

It’s easy from this outline of a biography to see where Huang gets his deep sympathy for people caught in global disruptions and tossed into encounters with American culture. And his unusual life and rich education have given him a sharp appreciation for the place of “race” in every rendezvous with American history.

Learned and playful, Inseparable draws on Huang’s personal experiences and his astonishing literary and historical knowledge. Inseparable has volcanoes, earthquakes and a solar eclipse; epidemics, revivals and slave rebellions. Bulwer Lytton, Flannery O’Connor, Tecumseh, Alexander Pope, King Rama II, Black Hawk, Mary Shelley, Victor Hugo, Nat Turner, P.T Barnum, Herman Melville, Mark Twain, Giambattista Vico, and Andy Griffith and Gomer Pyle all come into the story. Jane Austen makes a surprise appearance to introduce the seductive value of the good farmhouse Chang and Eng built to welcome their brides, Sarah and Adelaide Yates.

Scalpel-wielding doctors, who’d poked and prodded the twins when they were alive, held a post mortem to solve the mystery of their fleshy connection. The band between the two men had stretched to a little more than five inches, they knew. Cutting it open, they learned that the men shared one liver. (You can go visit the liver in its display case at the Mütter Museum in Philadelphia.)

But even with the question of the liver settled, curious minds wondered about the connection between the men and their wives. What kind of lovemaking went on in their big bed? Writers in the contemporary tabloid press weren’t afraid to speculate about the sex lives of the twins. Editors knew that readers gobbled up sensational stories of polygamous Mormons and bought flashy newspapers put out by New York’s sporting press. Some joined communities where couples swapped partners, inventing new forms of marriage.

Huang quotes a few of the writers who tried to imagine the sex lives of the foursome. But he turns to a host of literary allies to get at the complex and contradictory humanity of these two men, tied together, who made their way through an America divided by race, region, gender and wealth. The normal and not-so normal. Chang and Eng began their public life as freaks on display, servants indentured to white showmen. They wound up prospering as North Carolina farmers, fathering many children, and profiting from the lives and labor of dozens of men, women and children they owned as slaves.

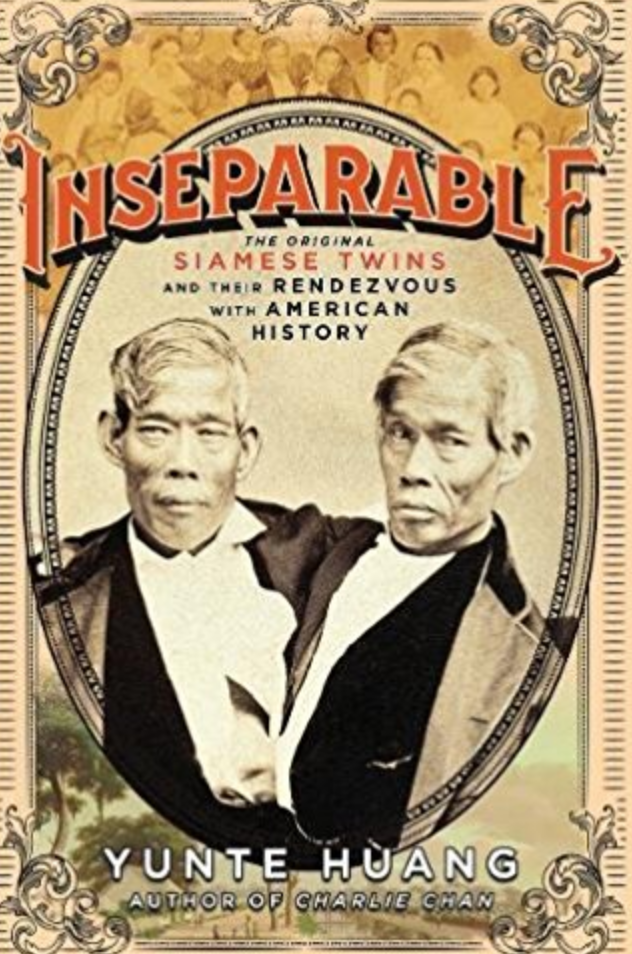

Still, a humane undercurrent lingers in the story, captured somehow in the portraits Huang uses to illustrate Inseparable. The twins appear in woodcuts and lithographs from the early days of their performance and in a photograph by Mathew Brady taken near the last. Looking at these pictures gives you a sense of the long appeal of these men and their story. The fleshy membrane that connected them meant that in every portrait one stood with an arm thrown over the shoulder of the other—an affectionate gesture drawing us back to the strange story of the original Siamese Twins.

Ann Fabian is a cultural historian.