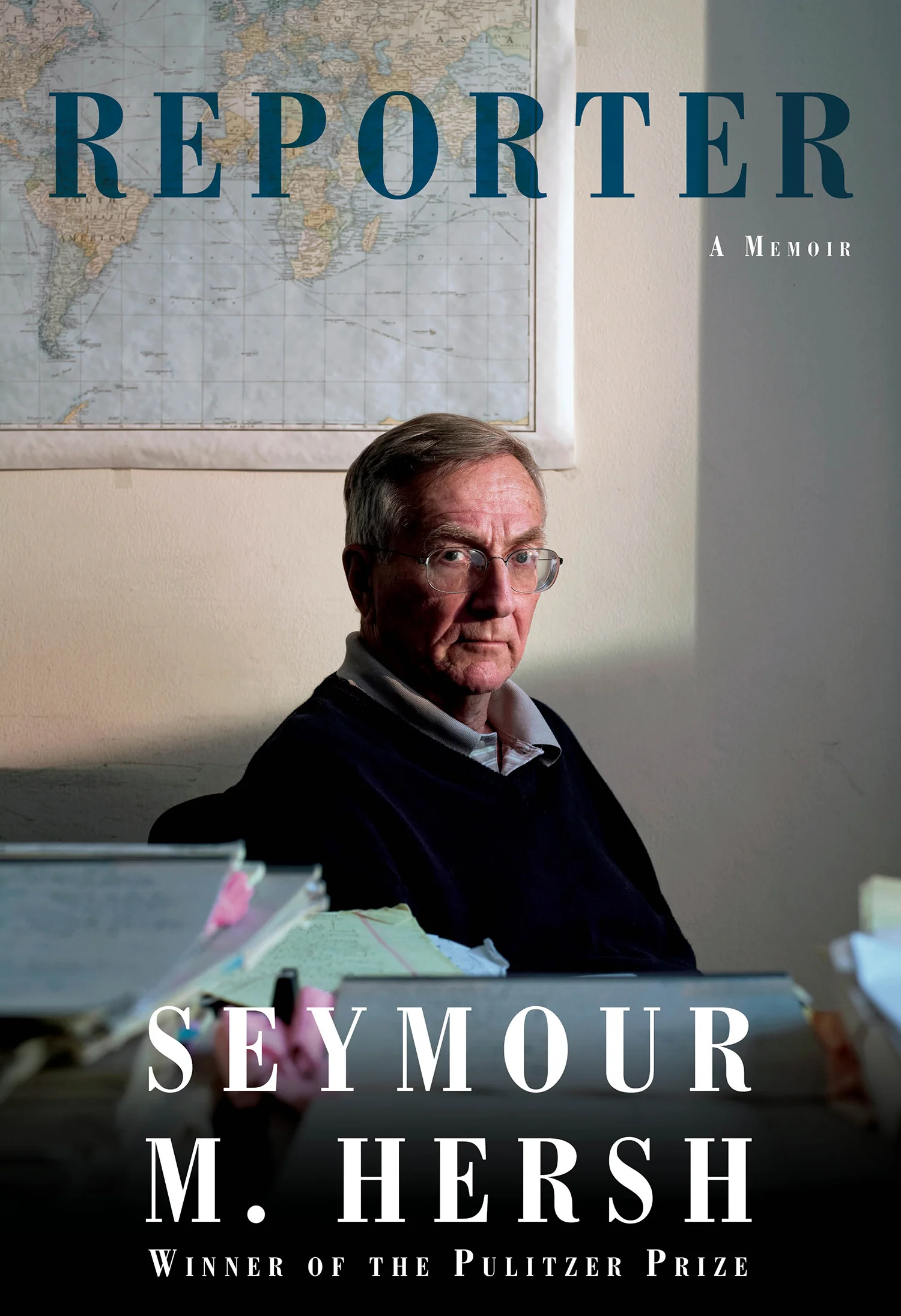

REVIEW: Journalist Seymour Hersh's Newest Intriguing Subject: Himself

/Reporter: A Memoir by Seymour M. Hersh

Knopf 368 pp.

By Charlie Gofen

Seymour Hersh long ago secured his place beside Woodward and Bernstein as one of our greatest investigative reporters. From his Pulitzer Prize-winning articles on the My Lai massacre in Vietnam to his exposure of the abuse of detainees at the Abu Ghraib prison in Iraq, Hersh has broken numerous huge stories over several decades, and his reporting has influenced public opinion, affected U.S. policy, and helped bring down a President.

Hersh recounts his life in journalism in his memoir, Reporter, and while many of the stories by this point are well known, he fleshes out details, adds some compelling anecdotes, and offers a peek at how he was able to scoop his peers.

His memoir also raises interesting issues of journalism ethics, although I doubt this was his intent. The hard-charging Hersh will deceive and sometimes even lie outright to get an important story. He barters with sources, often agreeing to withhold newsworthy information on the story at hand in return for getting a different, exclusive story. Much of his reporting relies on anonymous sources, making it difficult for readers to assess credibility. And when his primary employer deems his investigative work too flimsy to publish, he offers it to other journalism outlets with lower standards.

Hersh also engages in high-profile anti-war activities even as he reports on an ongoing war – conduct that many news organizations today would forbid or at least strongly discourage. “I knew I would be able to separate my personal views from my professional responsibility as a reporter,” he writes in his memoir. (The New York Times didn’t have an ombudsman back then to challenge Hersh’s impartiality, but the paper’s legendary editor Abe Rosenthal acknowledged the issue, at least in private, playfully approaching Hersh with the greeting, “How’s my little commie?”)

Hersh wrote his groundbreaking news articles in a straightforward manner, so he succeeded to some extent in keeping his personal views out of his reporting, but his decisions on which leads to follow were clearly affected by his own politics. In addition, he has been less concerned with providing objectivity or balance in his numerous public speeches through the years than in his published articles.

Still, Hersh’s biggest exposés, at least until the most recent decade, have proven accurate and consequential. He revealed the extent of the Pentagon’s chemical and biological warfare research during the Vietnam War, spurring President Nixon to announce that the U.S. would cease production of offensive biological warfare agents. He went on to break significant stories on Watergate, Henry Kissinger’s wiretapping of aides and journalists, domestic spying by the CIA, the secret bombing of Cambodia, clandestine U.S. operations against the Allende government in Chile, and, somewhat later, the Reagan administration’s Iran-Contra scandal.

And while Hersh at times employs situational ethics and ends-justify-the-means rationalizations, he does follow a code, grounded in holding powerful people in government accountable. As he writes,

I am in no way a fanatic, or a prude about lying, and realize that human beings lie all the time. We all know the clichés about the big fish that one caught or the low golf score. My brother and I learned early in life that our mother lied repeatedly, especially about store-bought cookies she claimed to have baked. Not a big deal. I happen to believe, innocently perhaps, that official lying or authorized lying or understood lying about military planning, weapons systems, or intelligence cannot be tolerated. I cannot look the other way.

One ethical rule that Hersh has always considered sacrosanct is not burning sources who wish to remain anonymous. His success in getting people to talk to him throughout his career no doubt has stemmed in large measure from their knowing they could trust him to protect their identity. (Hersh notes that he is working on a book about Dick Cheney but is unable to publish it for now because he feels an obligation to protect his sources who are still working in sensitive government roles.)

The most enjoyable aspect of Hersh’s memoir is his descriptions of how he went about reporting his biggest stories, particularly how he identified and developed potential sources and then persuaded them to talk so openly with him. His account of how he tracked down Lt. William Calley, the mass killer at My Lai, on a huge Army base in Georgia is a tutorial for young journalists on resourcefulness and doggedness.

Among the secrets of his success as a reporter: keep track of the retirement of key military leaders, who may become useful sources; know as much as you can about a person before talking with him; never begin an interview by asking core questions; and learn to read documents upside down when you’re chatting with a lawyer in his office.

Also, whatever your beat, seek out and cultivate those people who have the highest integrity:

I learned a lesson as a Pentagon correspondent that would stick with me during my career: There are many officers, including generals and admirals, who understood that the oath of office they took was a commitment to uphold and defend the Constitution and not the President, or an immediate superior. They deserved my respect and got it. Want to be a good military reporter? Find those officers.

Hersh is the rare journalist who has been the subject of a lengthy biography (Seymour Hersh: Scoop Artist, written by journalism professor Robert Miraldi and published in 2013). In fact, Miraldi’s book, which is quite good, includes many of the same anecdotes that are in Hersh’s book – one might say that Hersh was scooped on the telling of his own life story. I had hoped that Hersh would have offered more reflection and analysis in his memoir, especially given that Miraldi’s biography covered the basic narrative, but Hersh’s extraordinary career still makes for an absorbing read.

Hersh grew up on the South Side of Chicago, the son of Jewish immigrants who owned a dry-cleaning store. He was an inattentive student, but he was obviously bright and liked to read widely. After enrolling at a two-year junior college, he was discovered by a literature professor who convinced him to apply to the University of Chicago, where he ended up graduating with a major in English. He then spent a year in law school but found the studies uninteresting.

He landed his first job in journalism at the fabled City News Bureau, which provided much of the reporting for Chicago’s big daily newspapers and served as an invaluable training ground for hundreds of reporters. In his spare time, he would read all four Chicago newspapers daily as well as the New York Times. “I was smitten,” he recalls.

Hersh left City News to do his required Army service and then returned to journalism, starting and running a newspaper in suburban Chicago, and then taking reporting jobs for the wire services UPI and the Associated Press. He showed a desire from early in his career to tackle vital issues including civil rights and police corruption, but he also had a more whimsical side, adding a creative flair to less weighty stories. As he recalls, “when Sinbad, the lowland gorilla who was the main attraction at Chicago’s Lincoln Park Zoo, escaped from his cage and romped around the zoo before being felled by a narcotic, I led my rewritten story with `Sinbad the gorilla nursed a hangover today, just like anyone else not used to being on the town.’”

In the mid-1960s, when Hersh was still in his 20s, the Associated Press sent him to Washington, and he was eventually assigned to cover the military. He found the Pentagon pressroom “stunningly sedate,” with reporters toeing the official line, and he quickly shook things up with reporting that challenged government accounts about the Vietnam War. His role models were Harrison Salisbury and Neil Sheehan, both of whom reported critically on the war for the New York Times, and the iconoclastic I.F. Stone, who published an influential anti-war newsletter.

After a brief interlude working on Senator Eugene McCarthy’s anti-war Presidential campaign of 1968, he returned to journalism as a freelance reporter. The following year, a lawyer who had worked on the McCarthy campaign tipped Hersh off about the court-martialing of a GI for the mass killing of 75 civilians in South Vietnam, and Hersh dived into the My Lai massacre story that would establish him as a leading investigative reporter of his generation.

Soon after, the New York Times hired Hersh, and he not only distinguished himself with his reporting on the Vietnam War but helped the Times get back in the race uncovering Watergate after the Washington Post had taken the early lead. Hersh reported and wrote dozens of front-page exposés on Watergate for the Times. He describes his scoops as a “self-perpetuating process” in which his high-profile articles made him the go-to reporter for government officials to contact when they wanted to offer new information. It was a golden age for a crusading journalist, Hersh writes. “I was trying to find truth in a White House sodden with lies, deception, and fear.”

After Nixon had been forced from office, Hersh revealed that the CIA had engaged in widespread domestic spying against anti-war individuals and other dissidents – a story that President Ford’s aggressive Chief of Staff Donald Rumsfeld and his deputy, Dick Cheney, fought to bury. (Cheney considered trying to indict Hersh.)

It’s at this point in the narrative that Hersh offers up one of his best anecdotes of the entire book. Trying desperately to get additional space for one of his domestic spying articles, Hersh phoned Abe Rosenthal at 2 a.m. and, after Rosenthal’s wife informed Hersh tersely that “Abe’s left me. You’ll have to call him at his girlfriend’s house,” Hersh asked Rosenthal’s wife for the girlfriend’s name, obtained her unlisted telephone number, and called her demanding to speak to Rosenthal.

A minute later Abe got on the telephone. He was very angry but I didn’t care. I interrupted his bitching to say that his fucking newspaper had its head up its ass and I had been told there was not enough space for the CIA story. How much do you need? he asked. I said at least seven or eight columns, seven thousand or more words. What’s your phone number? he asked. I said, What number? Numbskull, he roared. The phone you’re using in the office. I gave the number to him and hung up. A few moments later Abe called and said I want you to know that tomorrow’s New York Times will have an extra page in every one of its 1.6 million copies. On one side will be a house ad and on the other side your cockamamie story. I muttered my thanks and he said, in response, “I am telling you right now that you are not going to tell anyone, and I mean anyone, about what happened tonight. You got that?” With that, he hung up. And we never discussed it again.

One of Hersh’s most challenging assignments at the Times was reporting on corporate fraud and abuse at media conglomerate Gulf and Western, which owned Paramount Pictures and publisher Simon & Schuster. The Securities and Exchange Commission had already found cause to go after the company, but for Hersh, taking on corporate interests proved more difficult than holding government officials accountable. “The experience was frustrating and enervating,” he writes. “There would be no check on corporate America, I feared: Greed had won out.”

Hersh left the Times and wrote a critical book on Kissinger and later became a correspondent for the New Yorker magazine, doing exceptional investigative work after the 9/11 attacks and, in 2004, exposing the prisoner abuse at Abu Ghraib. He also generated controversy with a gossipy book on President Kennedy and a book on the role of the U.S. in the development of Israel’s nuclear weapons program.

In more recent years, Hersh has written several provocative articles that have tarnished his reputation. In contrast to the landmark scoops earlier in his career, these more recent stories have lacked credible sources or documentation and haven’t been substantiated by other journalists’ subsequent reporting. Most famously, he alleged that the 2011 raid on Osama bin Laden’s compound was a vast conspiracy between the U.S. and Pakistani governments. In Hersh’s telling, Pakistan had captured the al-Qaeda leader several years earlier and had been holding him prisoner until deciding to sell him to the U.S. Tellingly, the New Yorker wouldn’t even run the article, so Hersh gave it to the London Review of Books.

It’s difficult to reconcile the newer version of Hersh with the reporter who nailed down his stories so effectively in the past, but this latest chapter doesn’t take anything away from his accomplishments. Hersh is to investigative journalism what the Rolling Stones are to rock music – essential from a historical perspective regardless of what you make of their recent work. His best reporting days may be behind him, but for anyone eager to read some fresh Hersh writing, try his memoir and you might find, you get what you need.

Charlie Gofen is an investment counselor in Chicago who has taught high school and been a newspaper reporter.