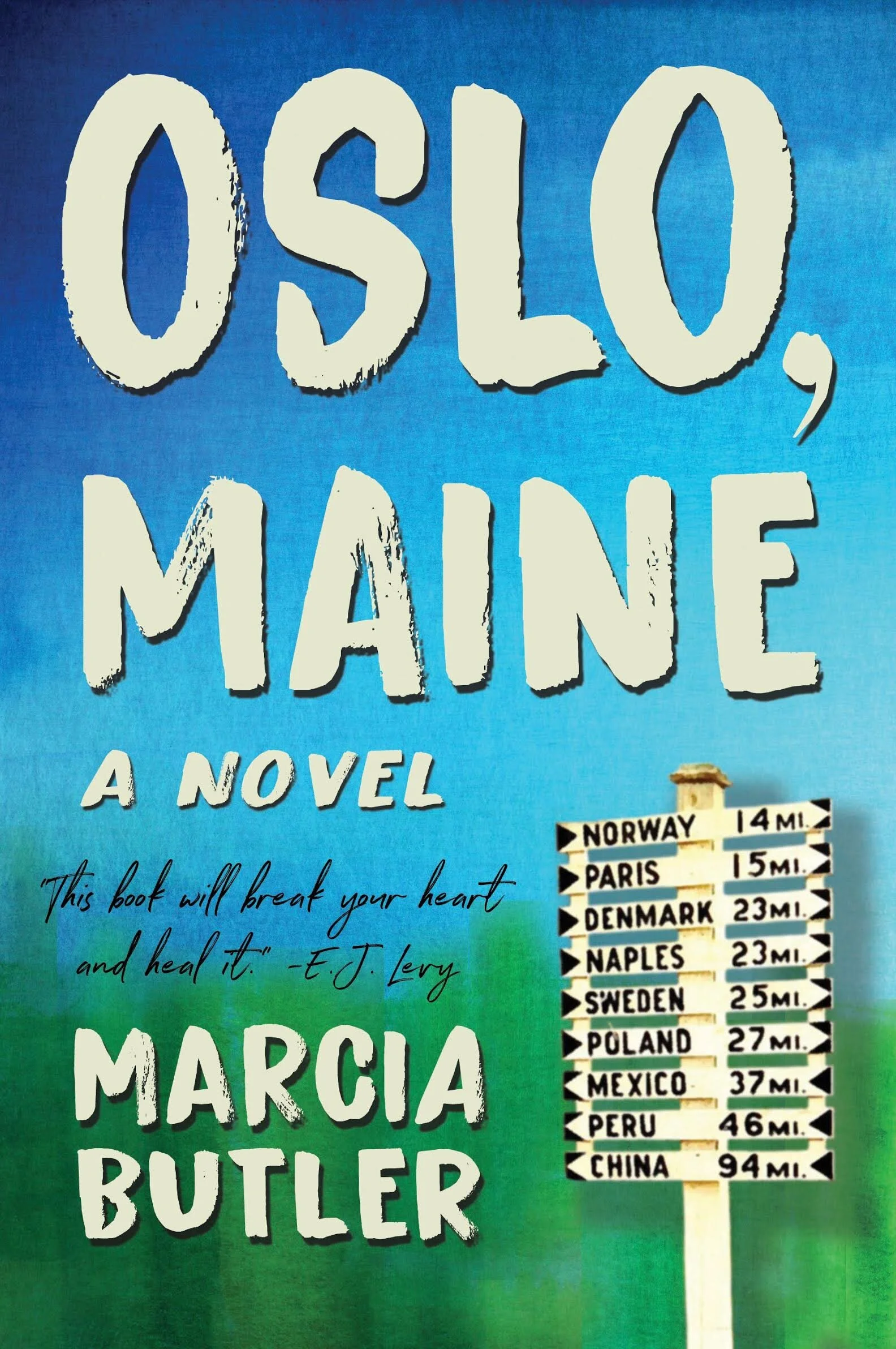

Q and A: Novelist Marcia Butler on the Writer's Process, Finding Inspiration, and Moose

/Marcia Butler, Bandelier National Monument, 2020

A pregnant moose lives at the edge of a struggling mill town and, from the first page of Marcia Butler’s lyrical and empathic Oslo, Maine (Central Avenue Publishing), this intersection invites danger and promise. When an accident between these worlds leaves 12-year-old Pierre with a brain injury that steals his memories as soon as he experiences them, his mother no longer recognizes the boy and his father finds him odd, delicate. Butler, who only began writing after a long career as a professional oboist, brings music into this novel through a violin teacher, who discovers Pierre’s memories stapled to the inside of a closet door. In a story that shows the beautiful mess of humanity and the burden of memory, music allows the child to slip into the Now. But music, as Butler explains in her interview with fellow author, Susan Henderson, lives in the very bones of the book. Their conversation for The National Book Review explores why John Coltrane provides the best description of her writing process, how ambition can be paralyzing, and what a moose can teach people about how to live.

Q: In your memoir, I remember becoming unnaturally obsessed with oboe reeds. And now, with Oslo, Maine, I’ve become obsessed with a moose. When, in the process of writing Oslo did you come up with the idea of letting a moose help tell the story? How did you find her point of view?

A: I’m glad I’m not the only obsessive person having this conversation! I was hooked on moose way before I began writing this novel. When I was an oboist, I spent many summers performing at a chamber music festival in central Maine. One day I saw a moose cow with her calf. She gave me a sidelong glance as if to say, “What are you doing here?” Love at first moose. I heard lots and lots of moose stories from the locals, but one was over the top crazy, a version of which lands mid-point in the book. Anyway, by the time I got around to writing Oslo, there was no question I’d have a moose point of view. A few author friends suggested I read other novels that took the point of view of an animal to get ideas of how that might work. Because it can come off as completely corny. But I didn’t want any influence. I felt like I knew my moose cold, and trusted that I’d find the right language so readers would understand what she sees. Her point of view opens Oslo—she’s pregnant and trapped so the stakes couldn’t be higher. The scene explodes, and what happens affects everybody in the book.

Q It’s interesting because she doesn’t just help move the plot but, as we see her surviving in her natural world, she’s showing us something about how you imagine her interior world.

A: What I’ve learned about moose, in general, is that they have a huge capacity to survive. They eat up to seventy pounds of leafless twigs a day in winter, which sounds pretty unappetizing. They’ll begin a gallop from a dead standstill. I’ve actually witnessed that. Unimaginable until you see it. Once I saw a moose emerge from a pond with a mouth full of grass and later found out that they’re born knowing that a certain plant grows only at the bottom of lakes. So, moose are really efficient and adaptive. But I also became curious about what her interior life might be like. And that was fun to create. My moose operates between managing hardships in nature and those caused by people, and a profound understanding of the spiritual realm. She exists among the living and the dead, simultaneously. Her human counterpart is a twelve-year-old boy named Pierre who figures out that when he plays the violin, he can go into a mental state that is completely in the present. I idealize, but I’d like to think that both the moose and Pierre have Buddha-like natures.

Q: So, to go deeper into your process, I’m curious—from the blank page to finding the shape of your narrative and who’s going to tell it—how do you get started and how do you find your way?

A: I don’t write from outline. I prefer to dig the tunnel blind. For Oslo, I had the inciting incident I mentioned before which I thought was powerful enough to wrap the novel around. So, I wrote toward that event and then away from it. Generally, I set my characters in a place, and then in motion. Sometimes they start saying their own words. As if they know their path better than I do! It reminds me of what it feels like to play chamber music when things go good-wonky on stage. You usually have several rehearsals where you develop a plan—how you’re going to interpret the piece. Such as when to play loud or soft, go faster or slower, and of course the general arc, or interpretation, of the music. That sort of thing. You walk out on stage with this plan in your head. Then, during performance, something else happens. One player might take a liberty that’s different, completely instinctual. And everybody goes to it simultaneously and in a split second.

It’s like this collective knowing, where everyone’s hyper-hyper-attuned. The music then becomes what it is truly meant to be. So, when this happens with a character, first you think—where the hell did that come from? And then you pay attention like mad. Because this is the juice, the thing that you actually need to know.

That’s how I proceed with my novels. I’m open to where my characters want to go, who they want to be, how they’ll operate within the world I’m creating. All of this pushes the story forward. In music and in writing not knowing is a beautiful place to be because, when you give in to it, you’re not an authority of your own work.

Q: What an astounding way to describe the process—and one that feels true for me, as well. When you walk towards the mystery, towards what you don’t know, that’s often where the magic is. Can you say more about not being an authority of your own work? I’m not sure I understand that.

A: Well, just because I’ve written three books doesn’t mean the fourth will be any good at all. Each book doesn’t necessarily build on the last. I purposely release the notion of authority based on past experiences. I step into it like a child. And so, by understanding that you are not an authority for all time, that’s when a more interesting picture can emerge. This doesn’t happen all the time, by any means.

Q: I was thinking, as a musician, you must have such a deep, internal sense of shape—the shape of songs, of compositions. Does that give you an instinctual understanding for how to shape your story? A: Yes, I think that is packed into me. There’s an implicit architecture to music. And I see it as storytelling too.

Q: Even jazz.

A: Oh sure, definitely. With jazz, melody and harmony act as the structure. Then, as each musician improvises, they’re playing with tension and relaxation—like flexing a fist. That becomes the story. When I write, this kind of intuitive architecture is operating in the background, always. And lately, it’s occurred to me that I can’t seem to separate music from my writing. In many ways I feel like a better musician now than I ever was as a performer. Which is weird because I haven’t played the oboe since 2008. I thought I was done with music, but it seems to have a hold on me.

Q: I’m glad it does. And I love the notion that you build toward the place you want to go, rather than waiting for some flash of genius.

A: Right! That elusive flash of genius. For me, it’s more a sense of “knowing” which only comes from grinding through that tunnel. It’s a relaxation into what is, finally, correct. I’m thinking about Coltrane’s “A Love Supreme.” Do you know that album? It begins with a gong, then he arpeggiates on perfect fourth intervals, then a four-note baseline comes in. This is the framework, or the structure, for a story he wanted to tell. For thirty-three minutes, you hear him travel through all twelve keys, drilling his tunnel, trying to find the gold. Coltrane knows there is no shortcut; you literally feel his search, every step of the way, almost note by note. It’s a miraculous composition. Spiritual. Truly groundbreaking. If you listen to Coltrane in his early years and then listen to “A Love Supreme,” you won’t recognize that musician. They sound like completely different artists. But they are one man who found transformation in the search.

Q: It’s such a great description of what it can feel like to write a novel… the searching. Because usually, when you have that first impulse, that first meaty idea, you think it’s going to take you all the way. But you might only get three pages out of it before you feel lost again. And then it’s this process of searching and chasing the heat.

A: Exactly. Chasing the heat. It’s like you’re sitting in a room that’s chilly. And then there’s this little thing that feels hot which relieves the discomfort for the moment. And then you’re immediately looking for the next one, right? That brings up another thing I learned as a musician. To find the gold in music, you have to live with that Mozart concerto for as long as it takes so that, when you do get on stage for the performance, you are literally telling not your story, but the composer’s story. You’ve gone beyond your own interpretation to what you believe, in that moment, might be what Mozart wanted. This takes time. The discipline to sit with the material again and again. So as a writer, I get on the page and whack away at it pretty much every day.

Q: Would you riff on two words for me? The words are potential and ambition.

A: Potential is something that’s infinite. It changes as you get older and get better. It’s like a fractal. It’s self-similar. Morphing and also expansive. Pure ambition is like this. A writer has published four short stories and, through the process, has identified an overarching theme between the stories. This discovery then prompts the writer to think deeply about what that theme means. Several new ideas come to mind. The writer then writes stories from an organic impetus. The drive is internal and feels imperative. With forced ambition, a writer has four short stories published and is encouraged to write six more because then it could be a collection and get published. The writer writes the stories from the motivation to get published.

Q: And then you just have a task.

A: Right. You try and fulfill it for the wrong reasons. It’s thinking about the end game before you have anything on the page. For me, that kind of ambition is totally paralyzing. And ironically, it can actually block potential.

Q: How are you different for having written this book? And for having finished it in the context of all that has been so upending about this past year?

A: That’s a lot to unpack. But needed, because how can we ignore the pandemic? The thing that has come up for me, in a more intense way, is empathy. For my moose. And for Pierre. All the kid wants to do is make a beautiful sound on the violin so he can manage his chaotic life. For all the people in the world who do bad things and still have a good heart. And it’s through writing about people’s faults and challenges that I can dig down into a world I never imagined before and come away knowing something. Something new. Maybe something optimistic. Actually, no. It’s not empathy or optimism. It’s love.

Q: Let’s end with this picture of you. I asked you to find a photo that captured something about your creative process. What is it about you standing on top of this ladder that feels connected to your writing?

A: It was taken during the pandemic. I think October. I’m in Bandelier National Park in New Mexico climbing the last of five vertical ladders to reach a cave where there are petroglyphs. My friend Tom has already reached the top cliff and took this picture. That day I remember feeling very young. Like I was open to anything. Yes. I’m holding on to this ladder and I’m not falling. And yes, I’m so damned brave. It takes bravery to write.

Susan Henderson is a six-time Pushcart Prize nominee, the recipient of an Academy of American Poets Award, and author of the novels Up from the Blue and The Flicker of Old Dreams, both published by HarperCollins. https://www.litpark.com