REVIEW: How the Bloody Battlefields of WWI Paved the Way for Modern Plastic Surgery

/REVIEW: Saving Face

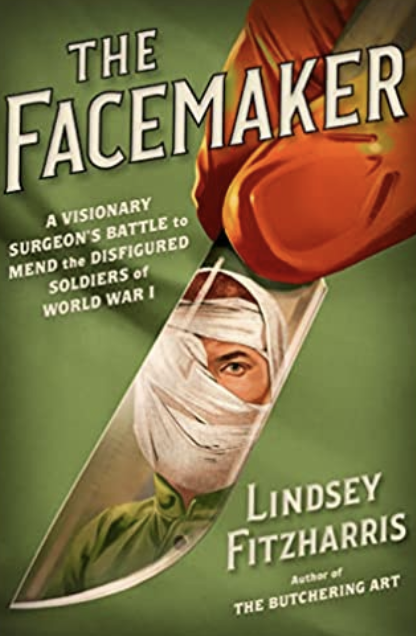

The Facemaker: A Visionary Surgeon's Battle to Mend the Disfigured Soldiers of World War I

By Lindsey Fitzharris

Farrar, Straus and Giroux 336 pp.

By Jim Swearingen

While somewhere between 8 and 12 million men died in World War I, double those numbers made it home wounded. The revolutionary efficiency with which new warfare technologies could maim quickly outstripped medicine’s ability to heal the “lucky” ones. Given the peculiarities of trench warfare and the human impulse to sneak a look over the parapets, about a quarter million men suffered horrific facial injuries.

Medical historian Lindsey Fitzharris’ new book, The Facemaker, relates the extraordinary developments in maxillofacial restorative surgery during the First World War. Fitzharris also captures the self-loathing psychology of those who had lost their facial identities in the trenches. Once handsome young men turned monstrous with combat injuries often withdrew from society, severed intimate personal relationships, abandoned pre-war careers, even committed suicide.

A British otolaryngologist (ENT) assigned to the Western Front, Dr. Harold Gillies, quickly appreciated the need for a specialized field hospital to address cavernous facial wounds: jaws, noses, tongues, cheeks, teeth, eyes blown away by bullets or shrapnel. Central to his revolutionary approach was the cooperation of surgery and dentistry to rebuild both physiological function and aesthetic form––restoring facial operations such as chewing, swallowing, and speaking, then crafting a face less grotesque in appearance. Huge advances in bone and skin grafting accelerated the ability of these faceless men to reintegrate into society shamelessly.

The face and jaw hospitals, which moved and grew throughout the war, sought to repair the physical damage to patients while endeavoring to make convalescents feel less self-conscious, removing mirrors, minimizing their contact with uninitiated visitors, and designating special places for the men to congregate away from the stunned gaze of civilians.

Alongside the story of new maxillofacial surgical techniques, The Facemaker captures the horrors of the Great War as Fitzharris introduces us to new patients and how they came to be wounded. She describes the terror of combat, the grotesque carnage, and the extraordinary valor of men who rescued one another from it. Fitzharris’ battle writing is stark and crisp.

She reintroduces us to the Somme, Passchendaele, Cambrai, battles synonymous with the unhinged viciousness of this war. The staggering number of casualties that poured into military hospitals provided doctors with a rich laboratory for experimentation in facial reconstruction.

Gillies himself is a refreshing study in leadership. In a field known for self-promotion, he deliberately created a collaborative team of surgeons, dentists, radiologists, anaesthesiologists, artists, photographers, as well as nurses. He also practiced that rare contradiction of strict adherence to rules while knowing exactly when to suspend them for the sake of morale.

Convalescing troops admired his identical care for privates and officers alike. And though he typically showed the stereotypical British pluck and stoicism, he could on occasion break down after losing a patient, a loss for which he always held himself personally responsible.

His natural bent toward procrastination served him well in a branch of surgery that could not be rushed. Indeed, some of his surgical failures came as a result of haste, rushing the pace of multiple operations at the prodding of his superiors, who desperately needed troops returned to the front, or his own patients, who eagerly wanted their new faces.

After the Armistice, Gillies passed up on a more lucrative and glamorous practice to bring battlefield facial reconstruction to a civilian population. Freak personal accidents inflicted similar facial damage to ordinary civilians and he continued to refine his craft, becoming the father of modern plastic surgery.

Where during the war he concentrated on bringing physical and psychic relief to his patients, he later embraced elective cosmetic surgery on its own merits. Using sophisticated skin grafting techniques, he performed the first phalloplasty on a trans man in 1949, skirting a British law that only sanctioned phallectomies.

All of these astounding advances that Harold Gillies and his multi-national, cross-disciplinary team invented owe a great debt to the carnage of World War I, as do today’s cosmetic and sexual reassignment surgeries. It’s a rich paradox that a field that has given so many people the aesthetic changes they seek has its roots in something so grisly.