REVIEW: Black Elk, the Sioux Holy Man Who Just Got His Name on a Mountain

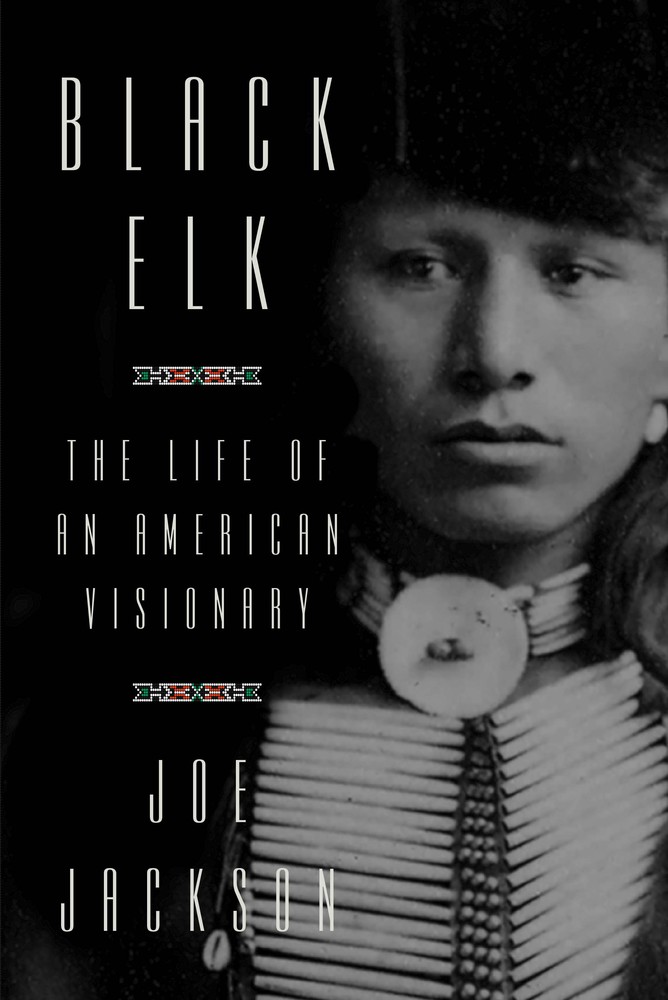

/Black Elk: The Life of an American Visionary by Joe Jackson

Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 624 pp.

By Ann Fabian

This past August, the U.S. Board on Geographic Names rechristened South Dakota’s highest mountain Black Elk Peak. The agency stripped the Civil War General William S. Harney off maps of the Dakota Badlands and replaced him with the Lakota healer and holy man.

Governor Dennis Daugaard didn’t approve. The name change was going to cost money, he said. It would confuse people, and for no very good reason. Harney, who had murdered a slave girl and killed Indians was hardly a sterling figure, but the governor suspected that “very few people know the history of either Harney or Black Elk.”

That won’t be true for long, if writer Joe Jackson has his way. His remarkably researched and beautifully told Black Elk: The Life of an American Visionary takes us step by step through the details of the seer’s long life.

It’s not all a new story. Those of us of a certain age cut our hippie teeth on Nebraska poet John G. Neihradt’s Black Elk Speaks. In the summer of 1930, Neihardt traveled to the Pine Ridge Reservation to meet the Sioux holy man. Neihardt returned the next spring with his stenographer daughter and with her help (and the help of Black Elk’s English-speaking son and several of Black Elk’s elderly friends) took down the old man’s stories.

Black Elk recounted his childhood in the 1860s, told of his travels with Buffalo Bill’s Wild West Show, and described General George Custer’s defeat at Little Big Horn. Black Elk took part in the Ghost Dance revivals of the 1880s, knew of Sitting Bull’s murder, and witnessed the massacre of his people at Wounded Knee in December 1890.

Those big events provide a kind of spine to the story, although the long account of Black Elk’s remarkable religious vision gives the book its heart. In that vision, young Black Elk had been taken to meet the Six Grandfathers and to see enacted a version of the Sioux cosmology—a vision of a unified universe. He carried that vision through his long life. When he sat with Neihardt in the early 1930s, the vision seemed to offer hope not only for the Sioux people, but also for all humanity.

Neihardt’s elegy for Native American life came out in 1932, sold a few copies and sunk out of print. New Age seekers found the book again in 1960s, and Black Elk Speaks became a classroom staple for a generation of students and a touchstone for spiritually minded readers.

Jackson goes back over Neihardt’s story, filling in the pieces that Neihardt and Black Elk left out. He provides context for the events Black Elk Speaks describes, things neither man could know: machinations at the Bureau of Indian Affairs, plans of generals and Jesuits, the constant coming of white settlers and the unavoidable tumult of American modernity. There are digressions on Jack the Ripper and speculations on the Epistles of St. Paul, but Jackson follows Black Elk’s story deep into history’s archives and the oral histories and Lakota memories of those who knew him.

The first half of Jackson’s book is an elaborate reworking of Black Elk Speaks, a kind of twice-told tale of Black Elk and his people. But Neihardt and Black Elk ended their story at Wounded Knee when Black Elk was just in his 20s. Black Elk lived for another 60 years, the decades that Jackson’s book covers in remarkable detail.

Black Elk was, as Jackson writes, “nothing if not adaptable.” There were good years when cattle prices were high. But prosperity didn’t last. He lost his eyesight. Tuberculosis ripped through his family, killing wives and children. Instead of Neihardt’s visionary tied to a vanishing west and a vanished people, Jackson gives us a modern man working his way through the obstacles of the 20th century.

Preserving his culture and communicating the complex spiritual vision that had shaped his life were Black Elk’s abiding concerns. In Jackson’s telling his determination to preserve his culture and communicate his vision provided a motive for everything Black Elk did. When the US government prohibited traditional native ceremonies and dances, Black Elk performed with Buffalo Bill and danced for twentieth-century tourists, adapting beliefs and cultural practices to modern venues. His controversial conversion to Catholicism gave him a chance to develop syncretic spiritual ways. Whether as a traditional medicine man or Catholic catechist, Black Elk worked to save his people.

And according to Jackson, Black Elk’s conversations with Neihardt were part of his strategy to preserve and perpetuate Lakota culture. Over the years, critics have questioned Neihardt’s motives and wondered at the authenticity of the stories he told. Jackson dismisses the doubters, insisting that the book was a collaborative project and explaining that Black Elk spoke to Neihardt knowing that the poet’s book would give voice to his spiritual vision.

Hurried readers might sometimes tire of Jackson’s detail, but his research has rewards, shifting in subtle ways the stories we thought we knew. In an “Author’s Postscript” published in Black Elk Speaks, Neihardt described a trip he took with Black Elk to Harney Peak. Long days of interviews over, Black Elk asked Neihardt to drive him to the mountain. In his vision, the Six Grandfathers had taken him there, but he had never climbed the mountain on his own.

Black Elk and his son, along with Neihardt and his daughters, headed to the Badlands. They took in a movie along the way, but Black Elk’s goal was to meet his spiritual mentors once more. “He’d prepared in advance for this address to the gods,” Jackson writes. “In his Vision, he’d been naked except for his breechclout, his body painted red, the color of the right road. But the girls were there and he didn’t want to embarrass them, so he stepped behind an outcrop and a few minutes later emerged wearing a bright red union suit commonly called long johns. Over that he wore a black or dark blue breechclout, trimmed in green, and on his feet high stockings and beaded moccasins.” Thunder rumbled in the distance and a small cloud brought the shower he’d predicted.

Black Elk must have been a patient man, guarding his vision as he let time move slowly through his 87 years. He was certainly a remarkable one. Despite Governor Daugaard’s misgivings, we should be happy to give Black Elk’s name to the mountain where he faced the rain in his red union suit.

Ann Fabian is an American historian working on a book about herpetologist Mary Cynthia Dickerson.