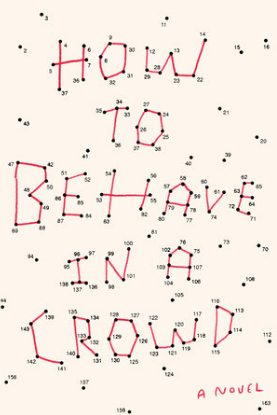

REVIEW: 'How to Behave in a Crowd,' a Too-Clever Novel of Family Life

/How to Behave in a Crowd, by Camille Bordas.

Tim Duggan Books, 336 pp.

By Rayyan Al-Shawaf

How to Behave in a Crowd, a new novel by Camille Bordas, is too clever for its own good. When not only the narrator/protagonist but virtually all the characters in a dialogue-heavy story prove impossibly droll, as is the case here, one is left with an exercise in glibness. In this novel, the reader must also contend with the jarring Americanisms and English-language wordplay Bordas inserts into her characters’ verbal and written exchanges, despite the salient fact that the story concerns a French family. To be sure, the author’s decidedly arch treatment of the Mazals gives rise every so often to a truly funny incident or encounter, some replete with witty banter. Yet such successful gags cannot right the listing tale, let alone reorient it.

How to Behave in a Crowd, which begins when narrator Isidore Mazal is going on 12, charts some two and a half years in his life. Dory, as he is known (despite his preference for Izzie), lives somewhere in the south of France. His family consists of a kindhearted but clueless mother, a politically idealistic but emotionally distant (and often absent) father, and five older siblings – all of whom, unlike him, are prodigies reminiscent of the kids in the film The Royal Tenenbaums. Needless to say, nobody in this family, child or adult, knows how to behave in a crowd; all are socially inept to one degree or another, which makes for some comical situations.

In fact, Dory’s siblings cannot even manage small talk. When Paris-based Berenice, the oldest, complains that her nail polish – which she applied for her PhD defense – didn’t come out right, Dory tells her that she should have gone to a nail salon. “I can’t do that,” Berenice answers him. “You have to have a conversation about your nails with the manicurist.”

Bordas fails to fully distinguish Dory’s siblings from one another, despite their separate academic pursuits and Simone’s theory regarding the futility of higher education (more on that later). With Dory himself, who is of course much more central to the tale, the author has fashioned a fitfully amusing character who bumbles through a generally humdrum adolescence. Dory emerges as fairly well-drawn, differing from his brothers and sisters in that he lacks a dazzling intellect, is marginally less awkward in social settings, and thinks in a literalistic and narrowly extrapolative manner reminiscent of certain strains of autism. “The day they explained time zones in school,” he recalls, “we were shown a map of Europe: it’s an hour earlier in Portugal than it is in Spain, the teacher said, and I looked at the map, and I thought it had to be roughly half an hour earlier in Madrid than in Barcelona.” When an older girl named Rose whom he visits out of town offers to sleep with the virginal Dory, he initially demurs, wanting his first sexual experience to be with someone he loves. “People said it was details that made you fall in love,” he notes, “and so I looked for details in Rose’s face, but all I could see was a nose, two eyes, a mouth, and a chin. I looked at her earlobes carefully, her eyebrows. Nothing stood out.” He has sex with her anyway.

Bordas tries, almost as an afterthought, it seems, to give her tale some direction – with mixed results. Toward the end of the first of the novel’s four sections, Dory’s family learns that his father, so often away on work-related trips whose purpose is never made clear to him (he fantasizes that his dad is a spy), has died of a heart attack. How the Mazals understatedly mourn their loss becomes a thread Bordas weaves through the rest of the story. Similarly, Dory’s gradual transition from phlegmatic cipher among overachieving prodigies to reasonably motivated instigator of change in a somewhat shell-shocked family – for example, trying in vain to pair his mother with a man through a dating website, as well as leaving town unannounced for a visit to his sister Berenice and a separate overnight stay at the home of the aforementioned Rose – begins to loosely tie together some of How to Behave in a Crowd’s episodic events. All this proves moderately engaging at best, and pretty boring at worst. Two subplots, one concerning local widow (five times over) Daphné, who is on her way to becoming the oldest person in the world, the other revolving around a growing friendship-of-sorts between Dory and depressive and anorexic classmate Denise, make little difference. Indeed, Denise’s sudden suicide feels like it belongs in another story altogether.

At least the author laces the proceedings with humor, black in the case of Denise’s grim outlook on life, mocking in the treatment of Dory’s insufferable sister Simone’s request that he repeatedly interview her for a biography she thinks he should write, and true-to-character when it comes to Dory’s hilariously flat observations. Of these last, a particularly memorable example relates to Daphné, whom Dory seeks out for German-language tutorials: “She laughed a little and then translated what she’d said in German and laughed again. Her laughter was the same in both languages.”

How to Behave in a Crowd is the author’s first novel in English. (Bordas, who today makes her home in Chicago, has written two previous novels, both in her native French.) One wouldn’t know it, though, from her fluency and obvious ease with the language. The problem is that she employs a distinctly vernacular brand of English. Indeed, even as Bordas displays an otherwise impressive facility with the American idiom, she damages her French characters’ credibility.

It would be one thing were the Americanisms restricted to Dory’s narration, given that he could conceivably have undergone a process of Americanization since his adolescence in France (related here in the past tense), but the phrases in question are often part of dialogue that takes place at the time. “Fucked-up shit,” “crazy motherfuckers,” “Have a good one,” “This…sucks it,” and “What’s up with that?” seem quite out of place, with formulations such as “Let me call 911” grating even further. In fact, Bordas doesn’t know when to quit, offering up English-language plays on words and misspellings as substitutes for the (never revealed) French originals. For example, a charity that organizes excursions to the beach for underprivileged kids, presumably from France’s interior provinces, is called “Let Them Sea.” Meanwhile, Rose’s linguistic infelicities are conveyed through spelling mistakes, such as “correspondance,” with which her letters to Simone and Dory are riddled.

Aside from this oversight (or deliberate and perhaps commercially minded attempt at cultural transposition), Bordas remains acutely aware of what she is doing. Playful, too. In a sly acknowledgment that How to Behave in a Crowd is hardly the kind of novel to elicit a strong emotional reaction from the reader, but also a sort of preemptive statement that it is not intended to, the author maneuvers German playwright Bertolt Brecht’s theory of Verfremdungseffekt into a classroom discussion. “Some choose to render it as distancing effect, some as estrangement effect, and some…as alienation effect,” notes Herr Coffin, Dory’s German teacher. He has just screened a German-dubbed version of the film Dogville – which takes place against a minimalist setting devoid of structures and props – for his class. “All the while, you’re not building an emotional connection with the characters,” he explains of Brecht’s theory, “but an intellectual one with the art piece itself.”

What, then, of the reader’s specifically intellectual engagement with How to Behave in a Crowd? Well, thought-provoking theories admittedly crop up here and there. Consider, for example, Simone’s belief, alluded to earlier, that higher education makes for a life very much akin to a funnel:

When you’re born, you virtually have an infinity of options, you get to swim at the top of the funnel and check them all out, you don’t think about the future, or not in terms of a tightening noose, at least. … [B]ut then little by little, you get sucked to the bottom. … It starts with the optional classes you elect in high school. … And then choices you could’ve made for the future get ruled out without you knowing it, and you sink down to the bottom faster and faster, in a whirlwind of hasty decisions, until you write a PhD on something so specific you are one of twenty-five people who will ever understand or care about it.

Unfortunately, because such intriguing (if pessimistic) theories surface only sporadically, they cannot sustain one’s interest. How to Behave in a Crowd is a largely tedious story peppered with intriguing conjectures and concepts. To be sure, Bordas doesn’t seem to take herself too seriously. In response to Dory’s stated supposition that the literary-minded Simone is planning to write a novel about their family, she replies, “Who would care for a novel about us?” That’s funny, all the more so for the self-deprecation on the author’s part. But does Bordas really want to know? She might be pained at how few are the people taken with this novel.

Rayyan Al-Shawaf is a writer and book critic in Lebanon.