LIST: Our 10 Best Memoirs and Personal Narratives of 2021

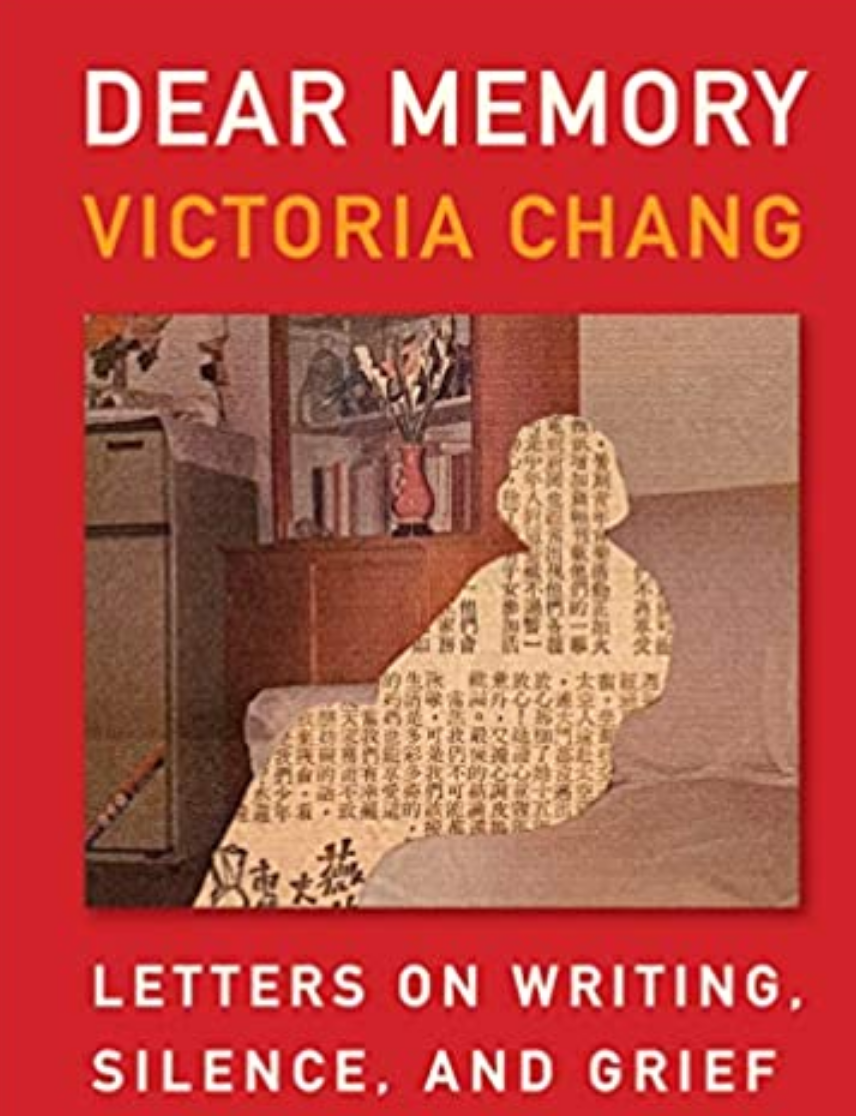

/1. Dear Memory: Letters on Writing, Silence, and Grief by Victoria Chang (Milkweed Editions)

This exquisite, genre-breaking wonder of a book is a visually intriguing, epistolary collage of old photographs, handwritten slips of paper arranged to be read as poems, official documents like a marriage certificate, mementos, blazing poems and literary inquiry. Chang’s wordplay and her eye for paradox and contradiction enrich this resonant, deeply rewarding exploration of memory and identity. She writes: “The epistolary form was a way for me to speak to the dead, the not-yet-dead, the sky, the wild turkey scurrying away, its white feathers waddling deeper into the woods, into myself, into a younger self, away from myself. Toward my dead mother. Toward my history. Toward Father’s silence. Toward silence. Toward death.”

2. Somebody’s Daughter: A Memoir by Ashley C. Ford (Flatiron)

What of the children of the incarcerated? Ford hits the best-seller list with her powerful and nuanced memoir as the daughter of a man serving a long sentence for rape, opening with his letter saying he would be released. Ford wisely focuses her account on his absence rather than the reunion, allowing her to chronicle her childhood with her brother in 1990s Fort Wayne, Indiana, and their beleaguered, short-tempered young mother, burdened as the family’s sole provider, as well as her demanding but loving grandmother. Ford evokes these relationships as they evolved, through her yearning for her father, reaching an understanding of the matriarchs in her life and coming into her own as a woman.

3. What Just Happened: Notes on a Long Year by Charles Finch (Knopf)

Finch’s chronicle of the vertiginous year beginning on March 11, 2020, nearly brings one to wish for pre-vaccination days if, that is, they could be spent in his pod, experiencing his sharp, revelatory cultural observations, polymathic curiosities, and keen sense of wit, irony, and moral compass. His register moves from rage to heartbreak in a paragraph, in a pastiche of “flatten the curve,” the Capitol mob, the War of 1812, the scarcity of hand sanitizer and spaghetti, buying stuff recommended on TikTok, and listening to Taylor Swift and Maren Larae Morris. Reflecting on the real genealogy of the world, Finch imagines a “far finer tracery of family trees” than patrilineal or matrilineal, one designed to include all the surrogates as real as parents, like his grandmother. He then reads Virginia Woolf’s postwar diaries in which she writes that “Thousands of young men had died that things might go on,” and he recalls laughing over what followed: “Must order macaroni from London.”

4. My Broken Language: A Memoir by Quiara Alegría Hudes (One World)

Playwright Hudes won a Pulitzer Prize for Drama in 2012 for Water by the Spoonful and wrote the book (and the screen adaptation) for the musical In the Heights. Her sharp, insightful memoir considers her roots in North Philadelphia and Puerto Rico, and their influence on the languages around her. Hudes’ prose is distinguished by its musicality “Music had been a window onto humanity, diasporic to the marrow,” she writes. She reconciled her parents’ distinct differences – her Jewish father and Boricua mother – and learned from her legendary playwrighting teacher, who won a Pulitzer for How I Learned to Drive in 1998. “The first thing Paula Vogel did was dispel me of the notion that I must be loyal to English,” Hudes recalls. “Language that aims toward perfection, she told me, is a lie.”

5. Halfway Home: Race, Punishment, and the Afterlife of Mass Incarceration by Reuben Jonathan Miller (Little, Brown)

Mass incarceration has an afterlife, one that Miller captures in his powerful narrative of “a supervised society – a hidden world and alternate legal reality.” Through vivid stories and evidence of this afterlife, which he witnessed growing up on the South Side of Chicago and as a sociologist and chaplain at the Cook County Jail, Miller describes “a new kind of prison,” one that “has no bars” and moves through families, denying opportunity to build a new future. As Matthew Desmond showed in his Pulitzer Prize-winning Evicted that eviction is not a one-time event, Miller demonstrates that the “vulnerability to surveillance and arrest” extends beyond jails, courts, and prisons. While he has found some making a life for themselves after serving their sentences, he acknowledges in heartbreaking prose that he is haunted by the reality that “almost everyone I visited at that jail looked like me, and they would come back over and over again.”

6. Smile: The Story of a Face by Sarah Ruhl (Simon & Schuster)

The talents of essayist and playwright Ruhl break the conventions of the traditional confessional memoir in her extraordinary personal narrative that recently won a spot on the 2022 Andrew Carnegie Medal for Excellence Longlist. Ruhl tells the dramatic story of after delivering twins and having her first play hit Broadway, developing Bell’s palsy. Paralyzing the left side of her face and rendering her unable to smile, the condition endured for a decade. Ruhl has a gift for crisp dialogue, dramatic pacing, sly wit, and sharp sensibilities.

7. How the Word Is Passed: A Reckoning with the History of Slavery Across America by Clint Smith (Little, Brown)

Smith, a writer for The Atlantic, brings an original and distinctive perspective to the consideration of slavery’s legacy as he draws from his experience as a teacher, journeying through nine sites that, in his portraits of these places and the people who inhabit them, reflect, shape, and grapple with collective memory as it evolves. Beginning with his hometown of New Orleans and its Robert E. Lee statue, traveling on to places as vastly different as Monticello, Angola Prison, and the “House of Slaves” on an island off Senegal, he draws on his powers as a poet to untangle strands of history. In his powerful and moving conclusion, Smith takes his grandparents to the National Museum of African American History and Culture where, he writes, the exhibits were not abstractions of their experience but “affirmations that what they had experienced was not of their imagination and harrowing reminders that the scars of that era had not been self-inflicted,” and what he heard from them was: “This museum is a mirror.”

8. Three Girls From Bronzeville: A Uniquely American Story of Race, Fate and Sisterhood by Dawn Turner (Simon & Schuster)

Turner’s beautiful memoir traces the trajectory of her own life and entwines it with those of her younger sister Kim and best friend Debra and wins its place on a shelf with classics The Other Wes Moore: One Name, Two Fates and Danielle Allen’s Cuz. At once a panoramic view of the Great Migration, and Turner’s “original three girls,” – her mother, aunt and maternal grandmother -- it is also an intimate story of the precariously narrow ledge of transition to adulthood, as Kim dies young and Debra lands in prison for murder yet, in a scene Turner beautifully renders, reconciles with the family of the man she murdered. Turner turns the lens on herself, rejecting her own belief that the daring Kim and Debra had made choices. “But it’s really a story about second chances,” Turner writes. “Who gets them, who doesn’t, who makes the most of them.”

9. Reclamation: Sally Hemings, Thomas Jefferson, and a Descendant’s Search for Her Family’s Lasting Legacy by Gayle Jessup White (Amistad)

Aunt Peachie was right! After at first dismissing her aunt’s family lore that the Jessups were descended from Thomas Jefferson, the author of this marvelous memoir embarks on a sleuthing mission peeling back layers of history and accruing evidence that she is a direct Jefferson descendant, confirmed by DNA in 2014. White builds on Annette Gordon-Reed’s landmark history, The Hemingses of Monticello, which proved the relationship between Jefferson and Sally Hemings, an enslaved woman at Monticello and the half-sister of Jefferson’s wife. White’s memoir is enriched by her exuberant charm and conversational tone as she charts her own mission of self-discovery in the tangle of American racial history.

10. Crying in H Mart by Michelle Zauner (Knopf)

This rich, vibrant, candid, raw memoir hits the best-seller lists, reflecting its universal connection for mothers and daughters. Readers of The New Yorker will recall Zauner’s 2018 essay in which the Korean American musician recalls a visit to an Asian American supermarket with her mother, Chongmi, which forms the first chapter in Zauner’s polyphonic memoir. Zauner’s Korean mother met her white father in Seoul, and eventually they landed in Eugene, Oregon. Mother and daughter had a contentious relationship, arguing over Zauner’s musical ambitions, which she successfully fulfilled as founder of indie rock project Japanese Breakfast. They reconciled after Chongmi’s cancer diagnosis, which led Zauner to grieve and understand how together they were searching the supermarket for ingredients that would sustain and bind them.