Review: The Amazing Adventures of Ruth Bader Ginsburg and Sandra Day O'Connor

/By Eileen Hershenov

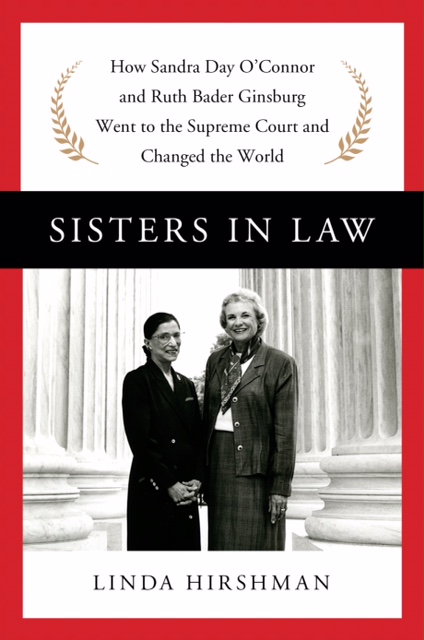

Sisters in Law: How Sandra Day O'Connor and Ruth Bader Ginsburg Went to the Supreme Court and Changed the World

By Linda Hirshman

Harper, 416 pp., $28.99

Apart from being the first two women on the Supreme Court, what did Sandra Day O’Connor and Ruth Bader Ginsburg really have in common? Was there any special bond between them? And did they create a synergy that advanced women’s rights further than either could have alone?

These are among the questions at the heart of Sisters in Law, lawyer-historian-philosopher Linda Hirshman’s fast-paced and sure-footed journey through O’Connor and Ginsburg’s careers. At first glance, their lives appear quite different – the Republican state legislator born on an Arizona ranch and the Brooklyn-born Jewish public interest lawyer and law professor.

Hirshman is careful to note the differences. Still, she makes a persuasive case that there was something special between O’Connor and Ginsburg – and that, as she writes, both rose to be historic leaders in the movement for women’s rights “at first Ginsburg directly and O’Connor by example.”

There were, from the start, strong parallels in O’Connor and Ginsburg’s careers. Each began with a supreme confidence that “she was naturally and by virtue of her talents entitled to run the show.” For O’Connor, it came from being a member of America’s governing class, and for Ginsburg, from being a member of the intellectual elite. One source of confidence they shared: both graduated at or near the top of their law school class – O’Connor at Stanford, Ginsburg at Columbia.

Despite an abundance of talent, they faced similar obstacles. O’Connor lost out on law firm jobs that went to men she had outperformed and was instead offered work as a legal secretary. Ginsburg was turned down for a Supreme Court clerkship by Felix Frankfurter, who did not want to hire a woman – and she, too, was turned away by law firms.

Neither forgot what she went through and, Hirshman says, both made something larger of the experience. The clarity they had about their own rightful place among elites enabled them “to see the injustice of women’s inequality in general.”

O’Connor’s rise was notably swift. When Ronald Reagan appointed her to the Supreme Court in 1981, he took an obscure Arizona Republican state party functionary, state legislator, and state court judge and put her in the history books. In an instant she became “the most famous symbol of a lived feminist existence on the planet.”

For years O’Connor was the swing vote to whom litigants in close cases addressed their arguments. But this alone does not explain her lasting significance for American law. Rather, Hirshman cites Aryeh Neier, former executive director of the American Civil Liberties Union, who hired Ruth Ginsburg, to argue that O’Connor may have embodied, more than any other jurist, the center of the country.

O’Connor could discern just how far American society was willing to go, and how much the Court itself could digest, and she wrote her opinions to hold that center. In this respect, she never stopped being the master legislator, adept at the politics of the possible – an expertise that too few other justices have exhibited, and none recently.

Ginsburg’s career before arriving at the Court was a world away from O’Connor’s. From 1972 to 1980, she was a founding co-director of the ACLU’s Women’s Rights Project and a Columbia law professor specializing in the same subject. Ginsburg was the preeminent leader of the legal movement for women’s equality, but in that role, she showed – no less than O’Connor – a shrewd sense of where the viable political center lay.

As a women’s rights advocate, Ginsburg was the architect of a legal strategy that brought to the Court a carefully chosen series of cases. It was an incremental approach similar to the one civil rights advocates had used. Ginsburg began with cases that were least threatening to the social consensus of the day. Indeed, to the dismay of many ACLU’s board members, the plaintiffs in some of the major gender equality cases she litigated were men.

Ginsburg’s brilliance was partly strategic: she recognized that, in an era when women’s equality was controversial, cases with male plaintiffs could appeal to male judges – while still producing decisions that would change the legal landscape for women. Another part of Ginsburg’s brilliance was philosophical: she understood that both men and women were trapped by traditional sex roles.

The stakes in the story rise when the first two female justices meet on the High Court. Hirshman’s ability to write clearly about the law without oversimplifying enables her to explain how O’Connor played defense and Ginsburg offense. (The sections on Ginsburg are, however, more vibrant, perhaps because O’Connor, whose health may be deteriorating, would not or could not cooperate and did not allow Hirshman access to her papers.)

O’Connor’s defense was on display in the abortion cases the Court heard during her tenure – as well as in sexual harassment and other women’s rights cases. In all of them, O’Connor did her best, Hirshman says, not to allow the Court “to roll the equality ball backward.” Notably, in 1992, she forged a centrist bloc with Anthony Kennedy and David Souter, resulting in a plurality opinion in Planned Parenthood v. Casey that saved Roe v. Wade, albeit with grave wounds.

If preserving Roe was a common cause for O’Connor and Ginsburg, it also showed where they parted ways. While Roe may still be the law of the land, in practical terms it protects a right that is now largely limited to women of means, like O’Connor herself. Roe’s unlikely savior lacked empathy for poor women and never found any state-imposed obstacle short of the complete criminalization of abortion (or spousal notification requirements, which clearly offended her) to be unlawful.

Unlike Ginsburg, O’Connor did not understand or relate to the burdens that vulnerable groups face. Hirshman attributes this deficit in part to the otherwise admirable values of individual resourcefulness young Sandra learned from her father on the ranch – and subsequently came to view as a reasonable expectation for everyone else.

There is another important difference between the first two women justices, beyond those of background and ideology: while O’Connor’s appointment and service on the Court made her a feminist exemplar, Ginsburg’s greatest contributions to the cause came before she got there. As a justice, her ability to give full life to her vision of women’s equality was stymied by the fact that she served on a Court with an entrenched conservative majority.

For that reason, Ginsburg’s true impact on equality under the law may not materialize for years. She has been writing eloquent dissents in 5-4 decisions in which the Court’s right wing prevails. The most recent came in last year’s “stunningly antiwoman decision” in Burwell v. Hobby Lobby Stores, in which the Court ruled that employers have a right to exclude birth control from employee health coverage.

There is a long and inspiring tradition of the ringing dissent from a wrongly decided case echoing down through history – and finally having its day. John Marshall Harlan’s noble dissent 1896 in Plessy v. Ferguson, in which the Court upheld the “separate but equal” doctrine, famously showed the way to Brown v. Board of Education.

So, too, it may be with Ginsburg, and her dissents, which have come not only in women’s rights cases like Hobby Lobby, but in Citizens United v. FEC, which allowed unlimited corporate political expenditures to inundate the political system, and Shelby County v. Holder, which gutted the Voting Rights Act. All of these, Ginsburg has observed, almost certainly would have come out differently if O’Connor had still been on the Court.

The fact that Hobby Lobby would likely have been a victory for reproductive freedom had O’Connor remained on the Court is, in a way, the ultimate proof of Hirshman’s thesis. Ginsburg, the lifelong liberal advocate for women’s rights, and O’Connor, her lower-key conservative counterpart, were a powerful combination. It is one we can appreciate all the more now that O’Connor is no longer there to provide the women of America with her critical swing vote – and to make sure the political center holds.

Eileen Hershenov, a graduate of Yale Law School, is Vice President and General Counsel of Consumer Reports. She spent a year after law school as a Karpatkin Fellow at the American Civil Liberties Union. The views expressed here are her own.

Follow Eileen on Twitter @HershenovEileen