REVIEW: Seeing Malcolm X as a Man for Our Troubled Times

/The Afterlife of Malcolm X: An Outcast Turned Icon’s Enduring Impact on America

By Mark Whitaker

Simon & Schuster 448 pp.

By Jim Swearingen

White folks should have listened to Black folks . . . a long time ago. Black folks have understood all along that there were never any legal protections that couldn’t disappear in an instant if Whites wanted something they controlled, whether it be a piece of land, a profitable idea, or a life dedicated to calling out injustice. As the United States trudges toward the precipice of fascism, the lessons of capricious lawlessness that came from Black activists like Malcom X forewarned all of us of the universal abuses to come.

And now, oppressions once reserved for non-White Americans are unfolding for anyone not in lock-step with the proto-fascist regime at hand. Look to Black history to instruct the rest of us on the threats of revoked citizenship, blocked voting rights, suspended habeas corpus, and midnight kidnappings. The defiant assertions of the Black Civil Rights Movement can instruct us all, if we will listen.

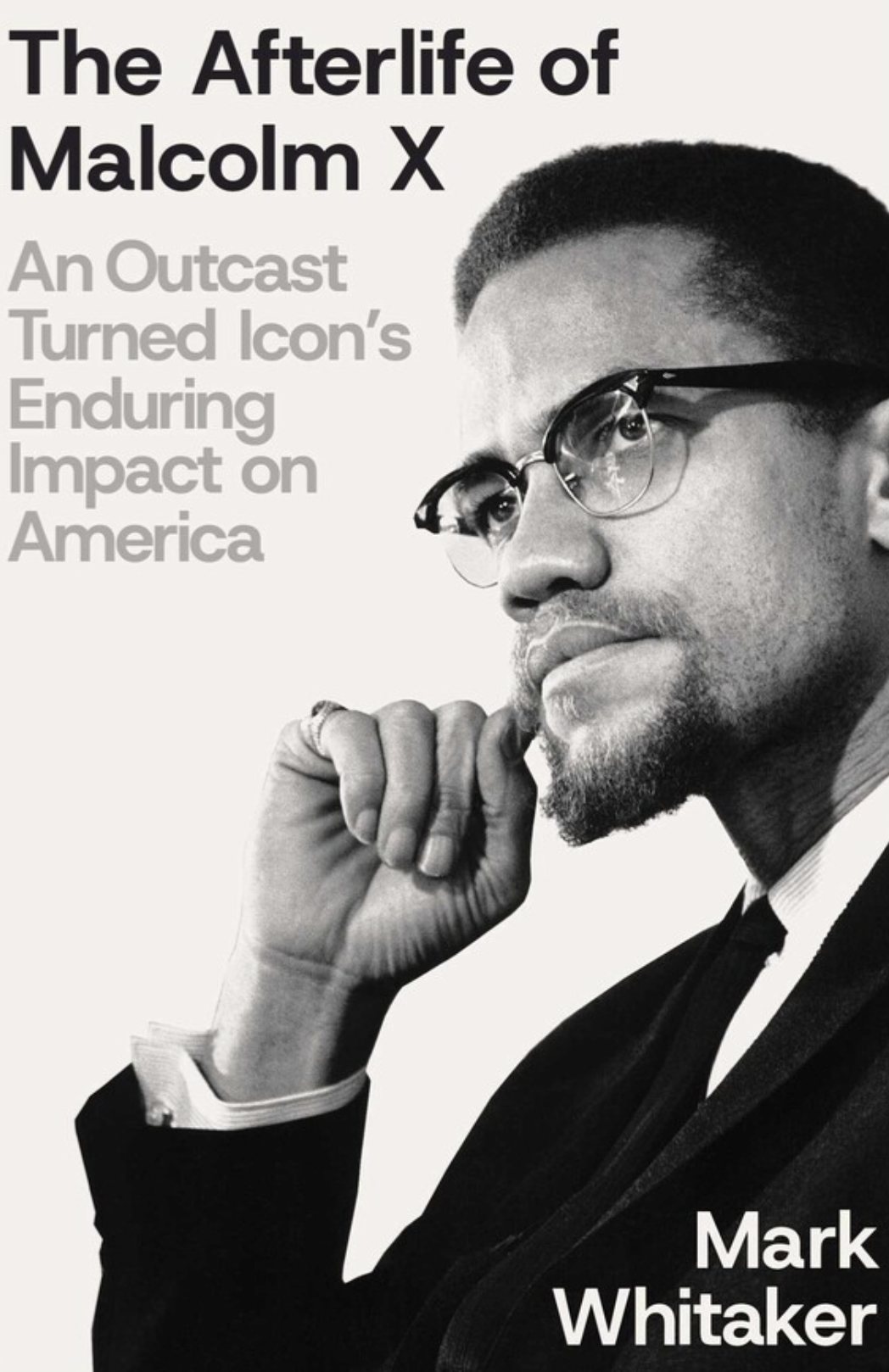

In The Afterlife of Malcolm X, timed to coincide with Malcolm X’s 100th birthday, former Newsweek, NBC, and CNN Editor Mark Whitaker traces the slain leader’s lasting imprint on popular and political culture – and his tremendous influence on generations of Black men, in particular. Unlike a standard biography, Whitaker begins with Malcolm’s assassination, then explores investigations into the murder conspiracy, the trial of three members of the Nation of Islam, and subsequent re-investigations and appeals. He goes on to document the impact of Malcolm X’s muscular racial pride on a host of Black talent.

It would be easy for a less accomplished writer than Whitaker to get lost in a sea of Malcolm esoterica, not to mention the lives and accomplishments of his disparate disciples. But Whitaker’s book is tightly organized and even-handed. He skillfully takes us down one road of 20th century Black history after another, then deftly returns us to the original storyline.

When Malcolm was shot down at the Audubon Ballroom in Harlem in 1965, actor and civil rights activist Ossie Davis eulogized his virile influence saying, “Malcolm was our manhood, our living, Black manhood. . . . This was his meaning to his people.” At a time when White America was just beginning to move in sync with a more conciliatory, non-violent brand of activism, Malcolm defiantly declared such approaches to be capitulation, doing so with the fervor of a colonial-era patriot.

A recurring theme throughout the book is Malcolm’s ability to invigorate a beaten down population with zealous confidence in Black equality and an unrepentant disdain for White hypocrisies. For anti-Trumpers impatient with peaceful marches and congressional protestations of dismay, reading Malcolm’s words today offers a refreshing jolt of adrenaline, a brawny refusal to acquiesce in autocracy.

While Malcolm’s words indicted an oppressive White society blind to its complicity in the oppression, they also served, like Pastor Martin Niemoller’s lamentation, to warn the rest of us to the dangers of silence in the face of political coercion: A society that will grind its boot into a Black man’s neck with impunity will strangle the rest of us in time. Brutality in America has not remained so narrowly targeted. “There, but for the grace of your skin color goes you or I,” has quickly become, there, but for the grace of your ethnicity, or your sexual orientation, or your political affiliation. Through such a lens, Black subjugation becomes one step in the subjugation of us all. No one is safe. In time they will come for you, whoever you are.

Whitaker’s book is peppered with some of the most stirring quotes from Malcolm’s speeches, insights that inspired legions of Black artists, writers, film-makers, musicians, athletes, lawyers, politicians, as well as subsequent generations of civil rights activists, often from different points in his intellectual and political evolution. Thus, people as disparate as Muhammed Ali, John Coltrane, James Baldwin, Barack Obama, and Clarence Thomas all used Malcolm as inspiration along their incongruous paths to Black dignity and accomplishment.

As with any mythologized individual, the truth is more complex, the human consciousness and motivation more tangled. We take our heroes one-dimensionally, molding them to our needs. Whitaker shows how once Malcolm moved from living revolutionary to legendary icon, a multi-front battle ensued among various factions of the Black intelligentsia and entrepreneurs over not only who and what he was, but also how he should be remembered. Even Malcolm’s most ardent admirers began to fabricate words from the late martyr’s mouth or to market his brand as a financially profitable fetish.

Whitaker cuts through this mythology to remind us that Malcolm was no believer in the White liberal Shangri-la of racial harmony. He was–and remains through his writing–an elbows-out, hard-scrabble Black nationalist, make of that what you will. And now, he can also represent exactly what a large portion of anti-Trump America longs, a strident leader who refuses to bend to oppression. Malcolm never apologized for believing in our most sacred principles. He was always a bold, in-your-face champion of the American creed, pointing out the double standard of liberty and justice granted to some.

As Trump unleashes gangs of uniformed agents against his own citizenry, Whitaker’s tracing of Black intellectual genealogy establishes for a new generation why Malcolm matters – and remind them of his prophetic value.