5 HOT BOOKS: A Convicted Murderer Who Charmed Women, the Rise of NYC, and More

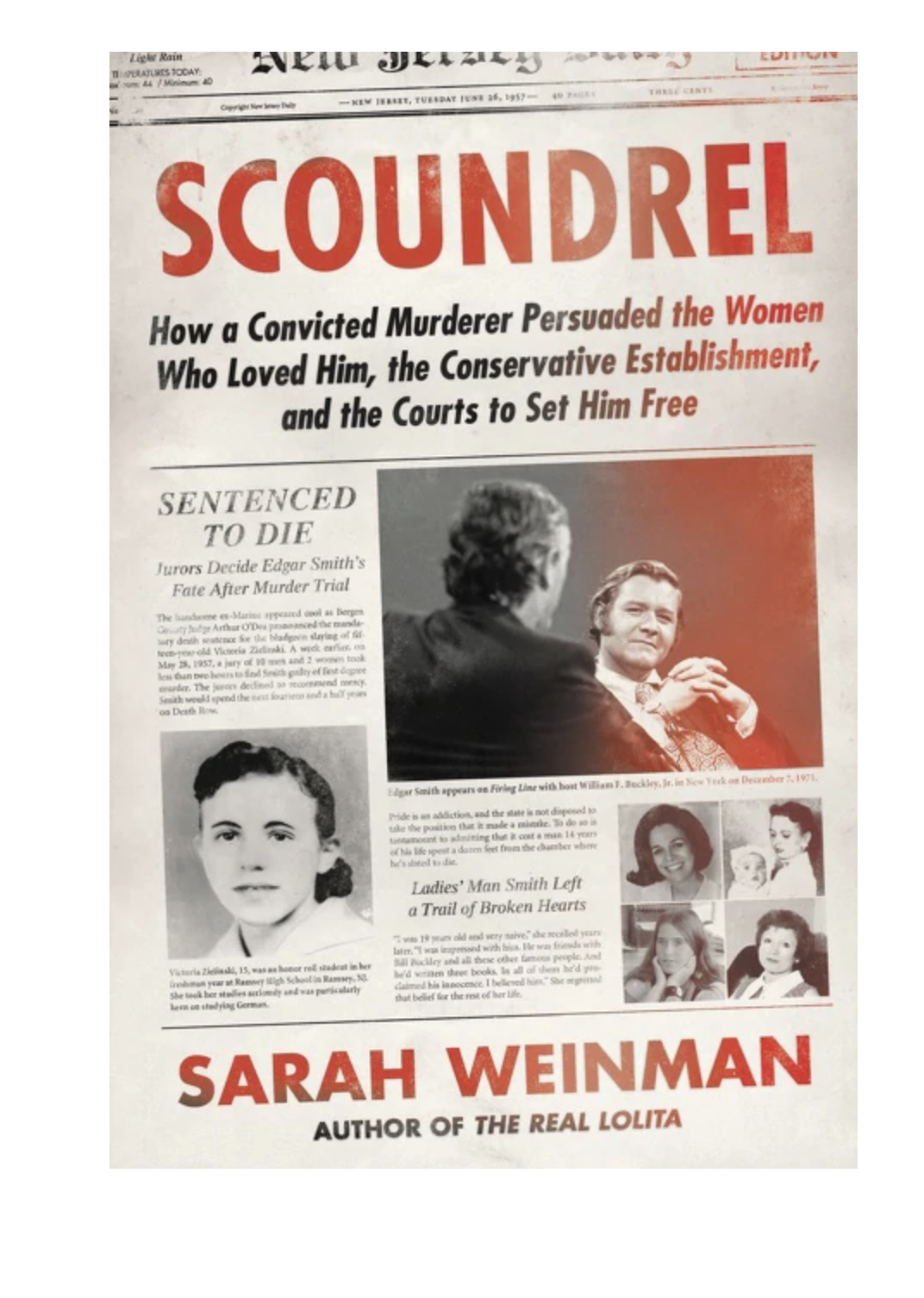

/1. Scoundrel: How a Convicted Murderer Persuaded the Women Who Loved Him, the Conservative Establishment, and the Courts to Set Him Free by Sarah Weinman (Ecco)

The literary and the lurid mix in Weinman’s captivating saga that seems unbelievable, although her prodigious research proves otherwise. Sentenced to death in 1957 for murdering a 15-year-old girl in New Jersey, Edgar Smith proclaimed his innocence, praised the National Review, which caught the eye of William F. Buckley, and over nine years of correspondence charmed him into an introduction to a female book editor. Smith carried on epistolary romances and was released from prison as a famous writer with celebrity status, until he kidnapped another girl. Weinman, who writes the crime column for the New York Times Book Review, brilliantly gets into Smith’s mind and plumbs details of the criminal justice system while writing empathically about his victims and raising important questions about how manipulative killers can win adulation in American society.

2. Manhattan Phoenix: The Great Fire of 1835 and the Emergence of Modern New York by Daniel S. Levy (Oxford University Press)

On the bitterly cold evening of Dec. 16, 1835, in Lower Manhattan, a fire broke out in a dry-goods store, raged for 10 hours, and destroyed 17 city blocks, and from those ashes, Levy tells the vivid, engrossing story of the city’s rebirth. This polyphonic social history captures not only the rise and influence of John Jacob Astor, creation of Central Park, flowering of the arts and the establishment of universities, while surviving the plagues of yellow fever and cholera, multiplying rats, and the reign of Boss Tweed, but also the fire chief who led his brigade to tamp the blaze. Levy keenly sees the persistent strife and tensions that arose, with nativist and Irish mobs battling one another – and free Blacks and new immigrants who they feared would take their jobs – as well as alliances, between bankers and the slave-holding South, and the ugly Draft Riots of 1863 that exposed rifts in the society that echo today.

3. Index, A History of the: A Bookish Adventure from Medieval Manuscripts to the Digital Age by Dennis Duncan (W. W. Norton)

In this surprising and engaging book, the humble index at the back of the book becomes a literary form, and its history is really about the relationship between time and knowledge. More than information science, Duncan argues the evolution of the index is a “history of reading in a microcosm.” 2. Duncan, a lecturer at University College London and an engaging guide through the iterations of indexes, contends that like acting, the work that goes into the performance should go unnoticed. “The ideal index,” he writes, “anticipates how a book will be read, how it will be used, and quietly, expertly provides a map for these purposes.”

4. The Swimmers by Julie Otsuka (Knopf)

Otsuka’s poetic novel begins with the swimmers at a community pool in the narrative “we,” aching with quotidian detail. Lives – and this brilliant work of fiction – are upended when inexplicable cracks develop in the pool’s floor, and cognitive-impaired Alice, determined that her routine will fend off dementia, is allowed one final swim before the pool closes. The vein of cracks opens a flood of voices in varying registers as the cold, bureaucratic language of nursing home care emerges, and Alice’s memory of her disappointments, her grief, and her Japanese family’s internment experience fades as her adult daughter comes to understand her own feelings of guilt and relationship to her parents.

5. The Berlin Exchange by Joseph Kanon (Scribner)

In 1963, with the Cold War at its height, Martin Keller, an idealistic Los Alamos physicist who has spent a decade imprisoned for sharing secrets with the KGB, is suddenly and mysteriously released in a British-East German spy swap, ending up in East Berlin and reuniting with his terminally ill ex-wife and pre-adolescent son who stars in a TV series. Add a slippery, wily East German married to Keller’s ex-wife plus some East German corruption, and Kanon has mixed a smooth and vibrant cocktail of suspense. Kanon blends the anxiety and paranoia of spycraft and, with psychological nuance and emotional heft, captures how political machinations on the world stage reverberate and shape personal life.