Q&A: The Reporter Who (May Have) Unmasked Elena Ferrante: "I Have No Regrets"

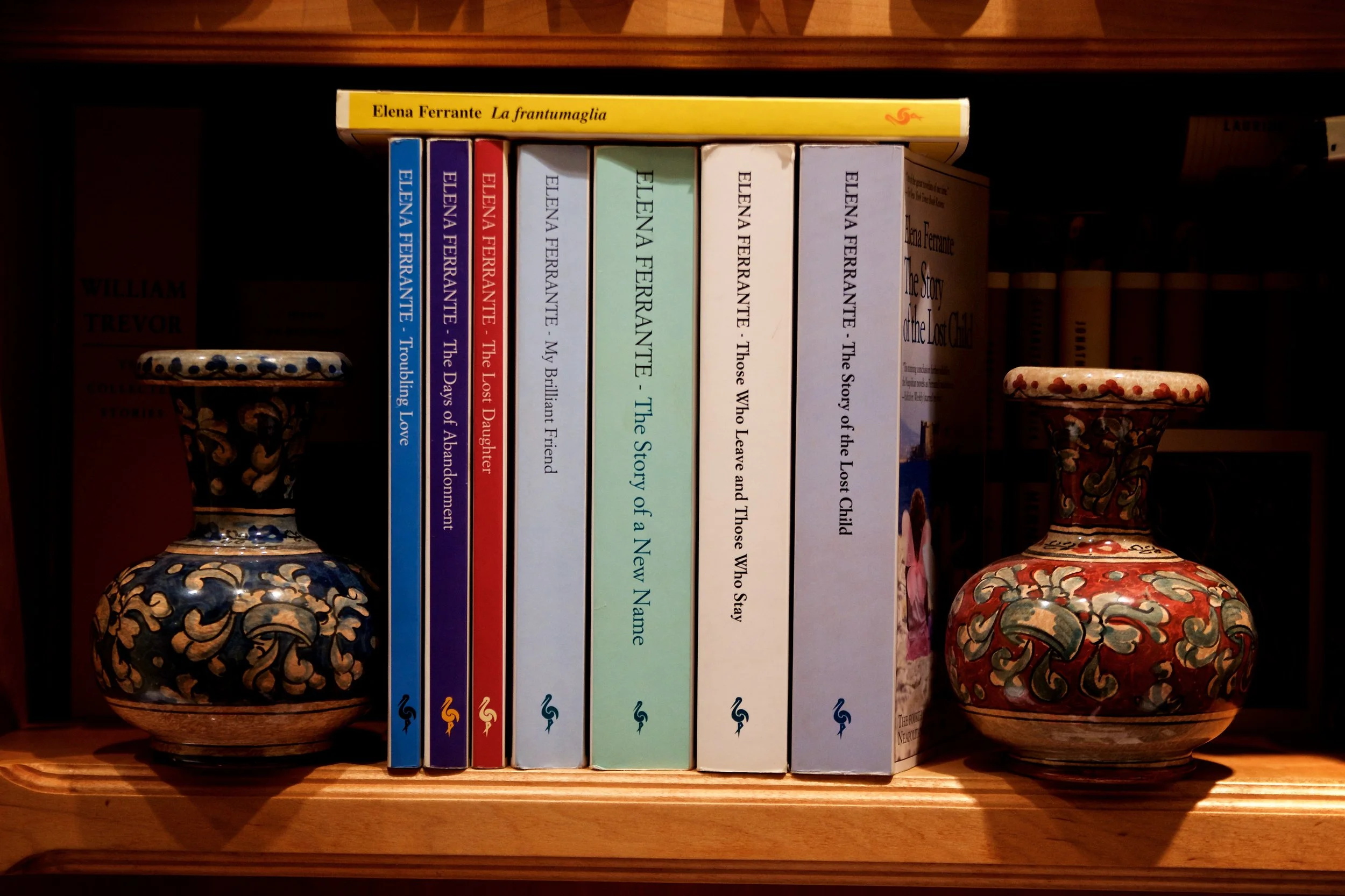

/Last month, Claudio Gatti, a journalist for the Italian newspaper Il Sole 24 Ore, published a two-part investigation into the identity of Elena Ferrante, the pseudonymous author of the internationally best-selling tetralogy known as the Neapolitan Novels. Gatti put forth compelling evidence, based on financial and real estate records, that Ferrante is the translator Anita Raja (though his identification remains, at this point, only a theory). The articles were timed to coincide with the November publication of Frantumaglia: A Writer’s Journey, a collection of Ferrante’s letters, essays, and correspondence.

Gatti has asserted that Ferrante’s numerous interviews with reporters, along with her decision to fictionalize her background in those interviews, made her a public figure worthy of a journalistic inquiry. I wrote a review of Frantumaglia on this site that was critical of Gatti. He contacted me, offering to talk about the subject, and I suggested a Q&A that we conducted through email. Several days later we met for a follow-up conversation, and this interview is the product of our correspondence and meeting.

In a wide-ranging discussion of more than three hours, we debated the nature of truth in non-fiction and fiction, which seemed to me to be at the heart of the difference between Ferrante, the fiction writer insisting on anonymity, and journalists, who for decades have inquired about her identity. I was reminded of the poet Mark Doty’s simple and elegant definition of genre: one’s habitual way of making meaning.

Gatti, a passionate investigative reporter, makes meaning of the world through the accretion of facts on the page; he follows his journalistic instinct that facts validate reality. As a novelist Ferrante seeks meaning through the creation of her first-person narrators: “The stories that you tell, the words that you use and refine, the characters you try to give life to,” she writes in Frantumaglia, “are merely tools with which you circle around the elusive, unnamed, shapeless thing that belongs to you alone, and which nevertheless is a sort of key to all the doors.”

And the question of what is learned by knowing the author’s true identity remains as elusive as ever, depending on the lens with which one views the world. –Maria Laurino

Q. Last month you made global headlines after publishing a two-part investigation that seems likely to have revealed the identity of Elena Ferrante, who has chosen to write under a pseudonym for the past twenty-five years. There’s been nearly universal outrage among Ferrante’s fans after you named translator Anita Raja as the author of these works. Were you surprised by the fury your story unleashed?

A. I wasn’t surprised by the criticism, or its harsh tones. My stories often generate strong reactions by the subjects I deal with or their supporters, and since I knew that Elena Ferrante had very committed fans I also knew that some of them might have attacked me. But the risk of criticism wasn’t a deterrent, as I was convinced that my work would have enriched the readers. And I think it did, for those who read the entire two-part investigation.

I was surprised though by the nature of some of the accusations against me. In particular the accusations of sexism or, even worse, of having committed the literary equivalent of sexual assault. That was unexpected. And it is also completely unfounded, given the fact that when I started working on the story, like most people familiar with Rome’s literary circles, I knew that there were two possibilities: Anita Raja, or her husband, Neapolitan writer Domenico Starnone. My instinct was that it was Raja, but the odds were 50/50 that Ferrante could turn out to be her husband, therefore a man. In other words, I went after a mystery, not a woman.

Finally I was surprised by the hypocrisy of those journalists who fueled the ugly rhetoric that emerged from the blogosphere. I can understand that a discussion limited to 140 characters is unavoidably superficial, and as such it can turn nasty. But I did not anticipate that many journalists would simply act as an echo chamber for those 140-character attacks.

Q. Other than the barrage of press criticism, which I’m sure has been challenging, have you experienced any personal backlash, for example, awkward encounters with friends or relatives, since your articles were published?

A. All my friends were very supportive, many outraged by the vitriol. Of course they are all very nice and caring people. But, seriously, I think the reason they reacted this way was because they read the entire two-part investigation. I believe that people who did had a better chance of understanding what I was trying to accomplish and therefore were more prone to agree with what the cultural editor of Le Monde wrote to me – which is that my investigation was “an important work that advances the understanding of Ferrante books.”

Q. The Italian journalist Beppe Severgnini recently wrote an op-ed in The New York Times headlined "Italy's Open Literary Secret," which stated that quite a few Italians had suspected Anita Raja was Elena Ferrante. Do you agree it was an open secret? And if people did suspect it, why do you think they did?

A. Beppe is right. As I said, in the literary circles in Rome pretty much everybody knew that it was either Raja or her husband. Those circles are tight, everybody knows everybody, and the identity of the first worldwide-known Italian literary superstar after Umberto Eco couldn’t remain a secret for long. So, one of the main accusations against me – of having revealed Ferrante’s identity – is certainly baseless, because her identity was known to many.

Q. But why would they suspect a German translator who had never published a book of fiction?

A. A philological analysis and a computer analysis in 2005 led to Starnone. My investigation in part was, how could a man write this, this is a clear female sensibility. So I think half of the people knew it was a woman, and it came out of the same household. Anita Raja was not a writer but an amazing intellectual, someone who has translated Kafka, and she’s been Starnone’s companion for twenty-five years. They knew her and they knew her depth.

Q. During Ferrante’s decades-long back and forth with journalists questioning why she remained anonymous, she began to make up fictional stories about herself –- if, that is, Ferrante is indeed Raja. As you have pointed out, she said that she was a daughter of a Neapolitan seamstress; that Naples defined her childhood, adolescence and early adulthood; that she had sisters. None of these stories correlate with the facts of Raja’s life – her mother was a teacher, she grew up in Rome, she has only a brother. Why do you think she made up a background that corresponded with her fictional stories rather than remaining in the silence of a chosen anonymity?

A. I strongly feel that Anita Raja ended up in a bind, because of her publishers’ aggressive efforts to market her books and to make her an international success. I am referring to the many interviews she was asked to do, where of course she was forced to go through verbal contortions in order to respond to questions without revealing her real identity. More significantly, I refer to La Frantumaglia, the only non-fiction book by Elena Ferrante, published in Italy in 2003 as a “self-portrait” of the writer and just recently released in English.

That book was the result of a smart P.R. move by Sandra Ozzola, one of her publishers, who announced to the Italian press that she had written a “public letter to Elena Ferrante” encouraging her to respond to “the healthy desire of your readers to know you better.” Ferrante was basically asked by her publisher to provide pieces of personal information. Those crumbs of information of course were supposed to connect her to the Neapolitan setting of her novels. But it was a very problematic exercise that required a difficult balance between the truth that readers were made to expect and the need not to reveal too much information in order not to be caught. In fact I believe she was put in an impossible position. So she ended up with a patchwork of truth and lies that completely offset the declared purpose of the book, which was to respond to the readers’ desire to know more about who she really was.

For example, in the essay that gives the title to the book, she writes: “My mother left me a word in her dialect that she used to describe how she felt when she was racked by contradictory sensations that were tearing her apart. She said that inside her she had a frantumaglia, a jumble of fragments […] The frantumaglia . . . depressed her. Sometimes it made her dizzy, sometimes it made her mouth taste like iron. It was the word for a disquiet not otherwise definable, it referred to a miscellaneous crowd of things in her head, debris in a muddy water of the brain.”

I personally believe that this paragraph describes truthful events. The writer does not explain the origin of the intense emotions that tormented her mother, but I suggest that they came from the extraordinary personal experiences Goldi Petzenbaum, her mother, had as a young stateless Jew during World War II, which I talk about in the second part of my investigation. The problem is that the writer couldn’t say that because her identity would have been disclosed. So, she was forced to hide an essential piece of information from her readers.

Q. You are a respected investigative reporter. But people have been particularly upset that you applied investigative tools, such as tracking down property and financial records, to identify a private woman who has long asserted that her anonymity supplies the creative space essential to her work. Why did you feel that it was necessary to reveal who she was?

A. I am an investigative journalist and part of my job is to expose lies. For years the author and her publishers kept lying when they denied that the author was their German-language translator Anita Raja. But for me, settling that matter once and for all, was just the preface of my work. That is why I spent about a month and half following the financial traces left by the commercial success of the books and about three months analyzing which authors had influenced her writing and reconstructing her family history. In fact I believe that her mother’s life - the story of a woman who overcame the most horrible persecutions and the most difficult challenges - must have had a strong influence on all of her books. Ultimately Goldi Petzenbaum’s life was a story of survival by a strong woman. And what are The Days of Abandonment and the Neapolitan Quartet if not stories of survival by strong women?

Q. Would you have felt differently about making Ferrante’s identity public if she had not lied about her background?

A. I would not have done it if she and her publishers had not played hide and seek with the media for almost a quarter of a century. That wasn’t my choice, it was theirs. However, anybody who plays hide & seek should know that being caught is an integral part of the game.

They claimed that they wanted her books “to live for themselves,” but in reality they craved the attention of the media and arranged for interviews with publications from all over the world. Then, they published a work of non-fiction that, along with of the interviews, had a long essay presented as a self-portrait of the author that was full of misleading information. They couldn’t have it both ways for long.

I am not alone in thinking that. In her review of Frantumaglia, New York Times book critic Michiko Kakutani writes: “This book is a 384-page repudiation of her assertion that the text is ‘a self-sufficient body, which has in itself, in its makeup, all the questions and all the answers.’ … [And] the sheer volume of interviews here, the author’s often self-dramatizing discussions of her life (or that of the character of the so-called Elena Ferrante), and the very decision to assemble this book seem to fly in the face of her declaration that writing should have ‘an autonomous space, far from the demands of the media and the marketplace.’ In some of her letters, Ms. Ferrante sounds as if she were playing a cat-and-mouse game with the press, at once coy and passive-aggressive […] It’s ironic that this often annoying book of interviews and musings should — in its very superfluity — emerge as a ratification of Ms. Ferrante’s stated belief that ‘I don’t think that the author ever has anything decisive to add to his work.’”

In her review in the New York Times Book Review, Elaine Blair presents the same argument: “As Frantumaglia makes clear, Ferrante really has been a public figure. Not only has she given interviews all over the world — to The Paris Review, Vanity Fair and Entertainment Weekly, to newspapers across Europe and an abundance of Italian publications — but she has also published essays and a collection of her correspondence with the Italian director Mario Martone, who made a film based on her novel Troubling Love. Taken together, the interviews and the correspondence offer a chance to ask, beyond the question of her government-issued I.D., who is she?

Q. You approach the question of identity as a journalist – your investigation was undertaken with the assumption that Ferrante is a public figure and therefore the public has a right to know the truth of who she is. But isn’t there a literary argument to be made here? She is not a public figure making decisions that affect our lives, but an author using her imaginative space to create deep and resonant truths for her readers. What is your thinking as to why, other than natural human curiosity, the public should know who Elena Ferrante is?

A. I believe that knowing the artist, her history, cultural and social background, enriches a work of art. In fact, I would argue that not knowing who she is, poses strict limits to our understanding of her work. Knowing the young Dickens gives more poignancy to David Copperfield, and reading Pride and Prejudice one becomes eager to know the kind of person Jane Austen was.

As Adam Kirsch, the editor who won the Roger Shattuck Prize for Criticism, said some time ago, it may be “cool” to argue the case that knowledge of a writer’s life is a mere distraction from what really matters, which is the work, but “as soon as we identify two works by the same person, we begin to make connections between them — to notice similarities of subject and theme, treatment and technique. And since the biographical author is the only common denominator between the books, we cannot help developing at least a rudimentary idea about her.” My dwelling into Elena Ferrante’s life did not provide material for gossip. It did not reduce the writer to a celebrity. Rather, it used her life to explain and clarify factors that I believe shaped her work.

Q. Egoism is fundamental to any creative act – George Orwell lists it first among authorial motives in his essay “Why I Write.” Novelist Haruki Murakami talks about creativity and egoism in a forthcoming book, noting how creative people “constantly have to find those realistic points of compromise between themselves and their environment.” Elena Ferrante’s compromise was extraordinarily unusual in an age of relentless self-promotion; she cleared the space she deemed essential for concentration by removing the figure of the author from the process of publishing. Would you feel responsible if she stops writing?

A. Until she started writing the Neapolitan Quartet, she had very long breaks between books. So we will have to wait for a number of years before we know if she will continue writing. But the threat of not writing if exposed, was in my opinion quite exaggerated and self-serving. As far as I know, she wrote all of her books in the isolation of her study at home in Rome, which remains today as protected and secluded as it was before.

I don’t really see how Ferrante’s great ability to capture the inner lives of women should in any way require her to be shielded from the public view. It’s not that she needed to roam around anonymously in the street Naples. So, how could my revelation thwart more writing? And let’s be real, when the day comes, if ever, that Anita Raja admits to be Elena Ferrante, she will not become a target of paparazzi. She is no Angelina Jolie. She is a successful writer. The worst case scenario is that she will have to sign a few books. A small price to pay for the extraordinary media attention that fueled her success.

Q. But you are talking about a physical space. What about the psychological space that needs to be protected, a space that each writer approaches with his or her own singular conditions?

A. I’m a journalist not a writer. I have a very different mindset than a writer. I deal with facts. So maybe because of that, I fail to see the need for detachment between the person you are and the person who writes. As a journalist, you need to be in touch with the reality, nothing else. Maybe this is my limitation – that I don’t perceive the problem. I can’t imagine what she would need and cannot have as Anita Raja. Under the pseudonym of Elena Ferrante she proved to be an amazing writer able to create literature that has nothing to do with her life. I expect that she will be able to continue to do that as Anita Raja.

Q. Again, if we accept your compelling argument that Elena Ferrante is Anita Raja, you inform us that Raja’s mother is German-born, of Polish Jewish parents. You write that Raja’s mother, grandparents, and extended family experienced “pogroms in Poland, Nazi persecution in Germany, anti-Semitic laws in fascist Italy and the Holocaust.” This information suggests that Raja is, in some ways, a triple outsider in Italy and within the Italian literary establishment: her mother had to flee Italy to safety in Switzerland because of Mussolini’s racial laws; Raja is also of southern Italian descent, her father a Neapolitan, in a country in which northern elites have shown deep class prejudice toward the South – an issue that Ferrante has dealt with repeatedly in her fiction; and she is a woman in a predominantly male literary establishment, the wife of a highly regarded Neapolitan novelist. Did this information offer you further insight as to why she may have chosen to remain anonymous?

A. I do believe she is a shy, private person, as she said in a few interviews, and her history may explain that trait of her personality.

Q. Knowing everything you now know, do you have any regrets about publishing your two-part investigation? If the clock could be turned back, would you do it again?

A. I have no regrets. But sometimes I daydream of meeting Anita Raja, having a very civil conversation with her and giving her copies of the WWII-era documents about her family I found in the course of my investigation. I doubt it will happen. But it would be nice.

Maria Laurino is the author of three books on the Italian-American experience, The Italian Americans: A History and the memoirs Were You Always an Italian? and Old World Daughter, New World Mother.