Q&A: How Did We End Up with this Far-Right Supreme Court?

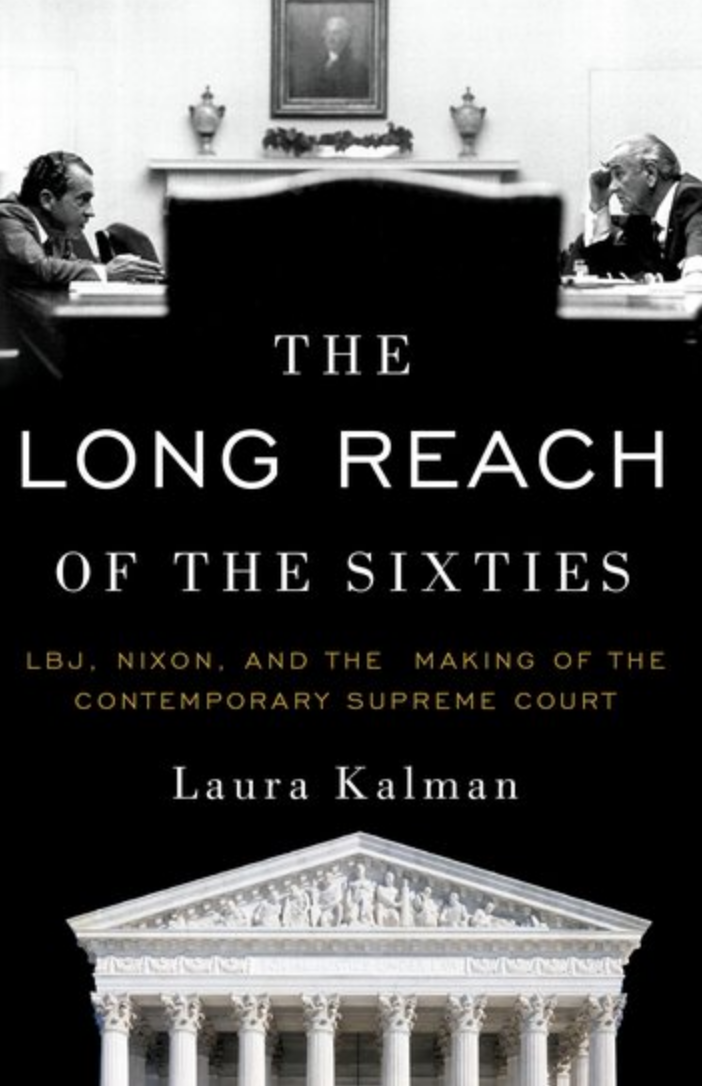

/Laura Kalman, professor of history at the University of California, Santa Barbara, is perhaps our most profound scholar of the ebbs and flows of American legal history. In Legal Realism at Yale, 1927-1960, she explored an enormously influential legal movement by examining its academic home base. In Abe Fortas: A Biography, she took a close look at an enigmatic liberal whose missteps paved the way for a conservative takeover of the Supreme Court. In her new book, The Long Reach of the Sixties: LBJ, Nixon, and the Making of the Contemporary Supreme Court, she digs deeper into the origins of the rise of a conservative Court that has lasted for nearly 50 years. Kalman spoke with The National about our rightwing Supreme Court, Republicans’ skill at court-appointment politics, and whether we should end lifetime tenure for Supreme Court justices.

1. Richard Nixon ran for President in 1968 with a promise to shift the Supreme Court to the right. Your book is in large part about how remarkably he succeeded. Why have the changes he wrought lasted nearly 50 years?

In so many ways, Washington is still Richard Nixon’s town. Nixon realized the symbolic value of the Warren Court as a target. He understood its usefulness in helping him work towards his goal of forging a majority party that melded together Republicans, white backlash Democrats in the South, and working-class ethnics elsewhere. The battles over nominations and confirmations that ensued during his and Johnson’s Presidencies created the contemporary Supreme Court appointments process, which I argue is rooted in the sixties, not in Reagan’s failed 1987 attempt to nominate Robert Bork.

Those fights transformed the meaning of the Warren Court in American memory too. Despite the fact that the Court’s work reflected, far more frequently than it repudiated, public opinion, these fights calcified the image of the Warren Court as “activist” and “liberal” in one of the places that image hurts the most, the contemporary appointments process. As a consequence, even when members of their own party controlled the Senate, two gun-shy Presidents in the late twentieth and twenty-first centuries, Clinton and Obama, appointed moderate progressives to the Court who rejected judicial “liberalism” and “activism.”

Although two of his own appointees, Lewis Powell and William Rehnquist, were practicing lawyers, Nixon also created the presumption in favor of nominating judges with whom the President had no real prior relationship. After his Administration forced the resignation of Johnson intimate Abe Fortas from the Court, the President summoned reporters to say that the Fortas hubbub had shown he must avoid “a political friend or…[in] the Washington vernacular, ‘crony.’” He also promised to replace Fortas with a judge. “Appellate and District Court experience gives an individual an edge,” the President said. From 1975 to 2010, the assumption that judges make better justices hardened into dogma. Many decided that Warren and those who came to the Court from outside the judiciary saw law as “politics.” Despite Justice Frankfurter’s reminder that the correlation between judicial experience and fitness for the Court is “zero,” federally elected officeholders disappeared and prior judicial experience became a prerequisite for every justice for the next 35 years.

Over the same period that the expectation of judicial experience bloomed, that of placing Presidential intimates like Fortas on the Court withered. To be sure, in nominating Elena Kagan, Obama selected someone without judicial experience whom he called a “friend.” Yet as Harvard dean and Solicitor General, Justice Kagan occupies a special place in the pantheon, and but for the Senate, she would have arrived at the Court from the great feeder of the DC Circuit. The nomination and confirmation of Justice Gorsuch suggests that Kagan’s appointment did not launch a new era but may have been the exception that proves the rule.

2. It has been argued that the Republicans are just better at Supreme Court politics than the Democrats. Johnson nominates Abe Fortas, and the Democrats end up losing that seat. The Republicans, on the other hand, refuse to confirm Merrick Garland and they are rewarded by getting Neil Gorsuch in the seat. Do think that disparity in tactical abilities has been true in the last half century?

Many would agree with the premise of that question. As John Dean puts it, the Democratic Party has played “beanbag” over Supreme Court appointments to the GOP’s “hardball.” The Warren Court has not proven useful to the Democrats, who have tried to respect and reject it by relegating it to the past. Recall that when candidate Obama called for justices with “empathy,” Kenneth Starr wondered if that was code for Warren Court types. Not so, said Obama, who maintained that 1960s judicial “activists…ignored the will of Congress” and “democratic processes.” Even as confirmation hearings feature nominees ritualistically swearing fealty to Brown v. Board of Education, they underline the bipartisan acceptance of the caricature of the Warren Court that Nixon and its other opponents advanced during the 1960s.

Meanwhile, the Warren Court has shaped the contemporary Republican Party, just as Republicans have shaped the Warren Court into an invaluable whipping boy. Understandably, Republicans have capitalized on hostility to it, sometimes to install strong ideological conservatives on the Court.

But consider how many more vacancies Republican Presidents have had on the Court than Democratic ones. Since 1968, the Democrats have had just four chances to nominate Supreme Court justices. Arguably, the Republicans, who got all the rest, muffed it. Significantly, Warren Court decisions remain intact, and there is still a right to abortion, which rests on the Warren Court’s Griswold decision.

3. Since 1968, the White House and Congress have passed from Democrats to Republicans and back multiple times. But we have had a conservative-dominated Supreme Court all of that time. Is that a problem?

It is if you’re a liberal, as I am! I don’t mean to be all gloom and doom. One could say that there has been a remarkable degree of consensus around the selection of justices. From 1969-2000, the Senate confirmed Burger, Blackmun, Stevens, O’Connor, Scalia, Kennedy and Ginsburg by overwhelming margins.

As Geoff Stone stresses though, the process has become more partisan and polarizing since 2000, and the existence of divided government that began in 1968 and has continued with intermittent interruptions ever since, doesn’t help. The experience of Merrick Garland suggests the United States might be headed for a future in which Presidents can only successfully nominate a justice when their party controls the Senate. That worries me.

4. Do you think we should be considering reforming how the Court or nominations operate in any way, for example by imposing retirement ages on the Justices, or limiting their terms on the Court?

I’m no fan of the contemporary nomination process. I thought the Republicans treated Judge Garland shamefully. In 1970, Mitch McConnell published an article claiming that the Senate “should discount the philosophy of the nominee” unless he were “a Communist or a member of the Nazi party.” Well, Judge Garland was no Communist or Nazi, but Senator McConnell and others would not give him a hearing. The refusal even to hold a hearing suggests how fraught the process has become.

I am intrigued by some of the reforms suggested in the selection of justices, such as retirement ages or term limits. But given FDR’s experience with Court Packing, not to mention the difficulty of accomplishing anything in Congress, I think they’re a hard sell.

5. If President Trump gets to fill Anthony Kennedy’s seat, or one of the liberals’ seats, we could have the most conservative Court in many decades. Where do you think the Court is headed now?

As an historian, I’m a poor prognosticator!