Q and A: Award-Winning Writer Anne Fadiman on Her Famous Father (And Other Topics)

/Anne Fadiman, Francis Writer-in-Residence at Yale University, a past editor of American Scholar and Best American Essays 2003, is known for her 1997 classic, and winner of the National Book Critics Circle Award, The Spirit Catches You and You Fall Down: A Hmong Child, Her American Doctors, and the Collision of Two Cultures, which chronicles the struggles of refugee family and their daughter diagnosed with epilepsy. Her most recent book is a memoir, The Wine Lover’s Daughter, about her father, Clifton Fadiman, the editor-in-chief of Simon & Schuster, book critic of The New Yorker, and host of the popular radio program Information Please.

Clifton Fadiman served for more than half a century on the editorial board of the Book-of-the-Month Club, longer than any other judge in its history. Fadiman received the National Book Award for Distinguished Contribution to American Letters.

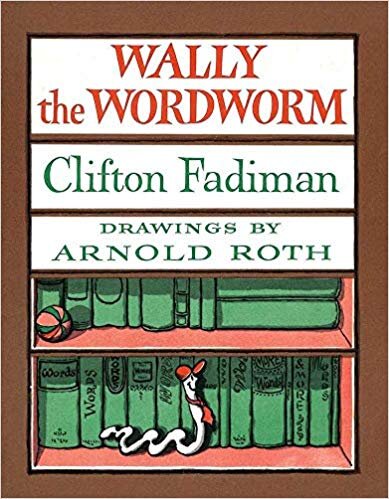

Anne Fadiman has revived one his great contribution to children’s literature: Wally the Wordworm, originally published in 1964, which is now back in print, published by David R. Godine, with an Afterword by Anne Fadiman. Wally lives on words and wriggles himself into a magical book: The Dictionary. Wally’s linguistic acrobatics are charmingly illustrated by New Yorker cartoonist Arnold Roth.

Anne Fadiman is married to George Howe Colt, author of The Big House which was a National Book Award finalist. She is the mother of two children. The family’s late dog was named Typo. She spoke about Wally the Worm with Madeleine Blais for the National.

Q: You recently helped bring about the reissue of a children’s book called Wally the Wordworm that your father wrote, with drawings by Arnold Roth, first published in 1964 and long out of print. What was the impetus for your drive to get it reissued?

Sure. First. I should explain what the book’s about. It’s a picture book for small, nerdy children about a bookworm — an actual, squiggly worm who eats words in books — whose appetite is insufficiently satisfied by the monosyllables in children’s books and who finds his way to the dictionary, where he happily gorges on words like “sesquipedalian.” Aside from a couple retellings of classical myths, it was my father’s only children’s book.

Whenever I did a reading in a bookstore from The Wine Lover’s Daughter, my memoir about my father, someone in the audience would invariably lament that his or her favorite book by my dad was out of print. The first couple of times, I assumed the book in question was of my father’s essay collections, but no. It was always Wally the Wordworm.

Q: What steps did you take to make this happen?

A: I was fortunate that after one of the owners of the Norwich Bookstore in Vermont heard an exchange just like the one I’ve just described, she contacted David Godine, a friend of hers who runs a small Boston publishing house that publishes beautiful books, and suggested that he republish Wally. David wrote me; I got in touch with the marvelous illustrator, Arnold Roth, who recently turned ninety; I wrote an afterword; and the book came out in October, a little larger than the original but otherwise looking exactly the same.

Q: How did this book come to be in the first place?

A: It grew out of a series of stories my father used to tell my brother Kim and me, to teach us new words. He’d sit in an easy chair in his study, and we’d sit on his lap or on an ottoman. Back then, the worm was named Bertram the Bookworm. When my father turned those stories into a book, Kim and I approved the metamorphosis into Wally, who seemed much cooler than Bertram---and we loved Arnold Roth’s illustrations. They still blow my mind.

Q: Did you read this book to your own children when they were little and how did they react to it?

A: I tried reading it to each of them when they were too young to appreciate it. I suspect there was also a certain stressful vibration in the room: YOU’D BETTER LIKE THIS BECAUSE YOUR GRANDFATHER WROTE IT! Anything other than ecstatic enthusiasm would have seemed insufficient, so I didn’t have the courage to try it again when they were a little older. Big mistake! If I’m ever lucky enough to have grandchildren, I won’t give up so easily on Wally.

I learned recently that one of my friends, the writer Nancy Pick, used to read Wally the Wordworm under the covers with a flashlight when she was eight. She says she might not have become a writer had it not been for Wally. Children who like Wally really like him.

Q: While the canon of literary memoirs contains numerous examples of writers grappling with family trauma or struggle, in The Wine Lover’s Daughter you break with the genre in offering a portrait of a parental relationship that — differing opinions on Bordeaux aside — is, well, happy. Indeed, your relationship had so few speed bumps that it took your indifference to wine to come up with what might seem like a significant betrayal. You profile your father with a tenderness that suggests you hope your reader will share your high esteem for him. You write, “If my father were forgotten, the balance of my world would shift so disorientingly that I’d lose my footing. I still check periodically to make sure he has more Google entries than I do. Phew.” Is this resurrection of a forgotten work part of your plan to ensure his Google entries exceed yours for a while longer?

A: You must have a copy of the hardback! (Thank you for the investment.) In the paperback edition, I had to update that passage because my Google entries had grown a little, while his had shrunk, and for the first time I had more than he did. I hated that, just as I’d expected I would. You’re right that one of the purposes of The Wine Lover’s Daughter was to prevent my father from being forgotten. Most of his work is out of print, but because I was able to quote liberally from his essays and letters, my memoir was a way to expose readers to his witty, articulate voice.

I’m glad you felt my book was tender, and I did love my father very much, but he was far from flawless---and his flaws are pretty conspicuous in The Wine Lover’s Daughter. He would have hated the book because, among other things, it revealed that he was unfaithful to my mother, that he was condescending toward women, that he was profoundly insecure, and that he wished he hadn’t been born Jewish.

Q: You once described your aesthetic as what sounds like the precise opposite of a blockbuster movie:

I have always felt that the action most worth watching is not at the center of things but where edges meet. I like shorelines, weather fronts, international borders. There are interesting frictions and incongruities in these places, and often, if you stand at the point of tangency, you can see both sides better than if you were in the middle of either one.

It sounds to me as if you might have inherited a sense of the power of the liminal from your father. How does that sensibility manifest itself in Wally the Bookworm?

A: Thanks for digging up that quote. It’s from my preface to The Spirit Catches You and You Fall Down, a book about the conflicts between a family of Hmong refugees and their American doctors. If I inherited a sense of the liminal from my parents, it probably came more from my mother, who was the first woman war correspondent in China and, like me, was interested in cross-cultural interactions. By contrast, my father was pretty firmly grounded in Western culture, which he believed contained everything he needed.

Wally as a liminal worm! I need to give that concept some thought. Perhaps the border he stood at, or even crossed, was the one that traditionally divides children’s literature from adult literature. Wally wasn’t content to stay in his designated bailiwick. That’s why he found the dictionary.

Q: We live in a culture where language is devalued and often imprecise. What, for instance, does “have a good one” really mean? And when did “not a problem” become a substitute for “you’re welcome” and why is it a crime against nature to use an expression such as “quid pro quo”? You don’t have to answer those questions, but more broadly, what factors contributed to the current cultural climate in which there is mistrust, if not outright hostility, toward people who prize learning and value language?

A: My father hated those phrases too. So do I.

I think the hostility toward learning and the precise use of language is populist at its core: Those privileged Ivy Leaguers with their fancy degrees and their fancy words think they’re better than we are. I can absolutely understand that point of view. If I’d been born into a different kind of family, I might feel the same way myself.

Q: And yet, we also live in a culture with countervailing forces that celebrate language: in plays like Hamilton, and in the works of wonderful new voices, books such as On Earth We are Briefly Gorgeous by Ocean Vuong and The Yellow House by Sarah Broom? Is there any way to get back what has been lost? Will the “deliciously acidulous riposte” ever come back in style?

A: I believe in “both/and” rather than “either/or.” I share your enthusiasm for Lin-Manuel Miranda and Ocean Vuong and Sarah Broom. I also love many of the works in the standard Western canon. I’m not sure we can reclaim what is lost, but we can certainly embrace new voices. The three you mentioned are the opposite of the “have a good one” mentality: They all use language with vividness and precision.

Q: The main character, Wally, is curious and, as he says, “voracious.” He spends his time finding wonderful words, big and small, to extol and then eats them. Wally “not only liked to eat words, he liked to meet them, greet them, and repeat them.” What were some of your favorite words as a child and what are some of them now?

A: Some of my favorite words are right in Wally the Wordworm! When I was a child, I particularly loved “syzygy.” I don’t know if my father included it because I liked it or if I liked it because it had originally been introduced in one of his stories about Bertram, but I remember chanting the spelling over and over.

Today my favorite words are the names of my husband, my daughter, and my son: George, Susannah, Henry.

Q: I think Wally should be a children’s play and I know the perfect young actor in New York (son-in-law of some friends) who does adult and children’s theater to direct it. Have you given this prospect any thought?

A: Not until this moment. Oooooooh!!!!

Madeleine Blais is the author of the forthcoming biography Queen of the Court: A Life of Tennis Legend Alice Marble, to be published by Grove Atlantic. As a reporter with the Miami Herald, she won the Pulitzer Prize for Feature Writing. She is also the author of several other books, including the memoirs Uphill Walkers and most recently, To the New Owners.