Q&A: Grand Design: Barry Pearce’s Short Story Collection, The Plan of Chicago

/"The short story seems in no danger of disappearing, hesitant as corporate presses often are when a writer, well known or otherwise, presents them with a new story collection for publication. Despite the form’s purported limitations, a range of writers that include George Saunders, Jonathan Escoffery, Lucia Berlin, Morgan Talty, and Claire Keegan have published much acclaimed and commercially successful collections in the last decade.

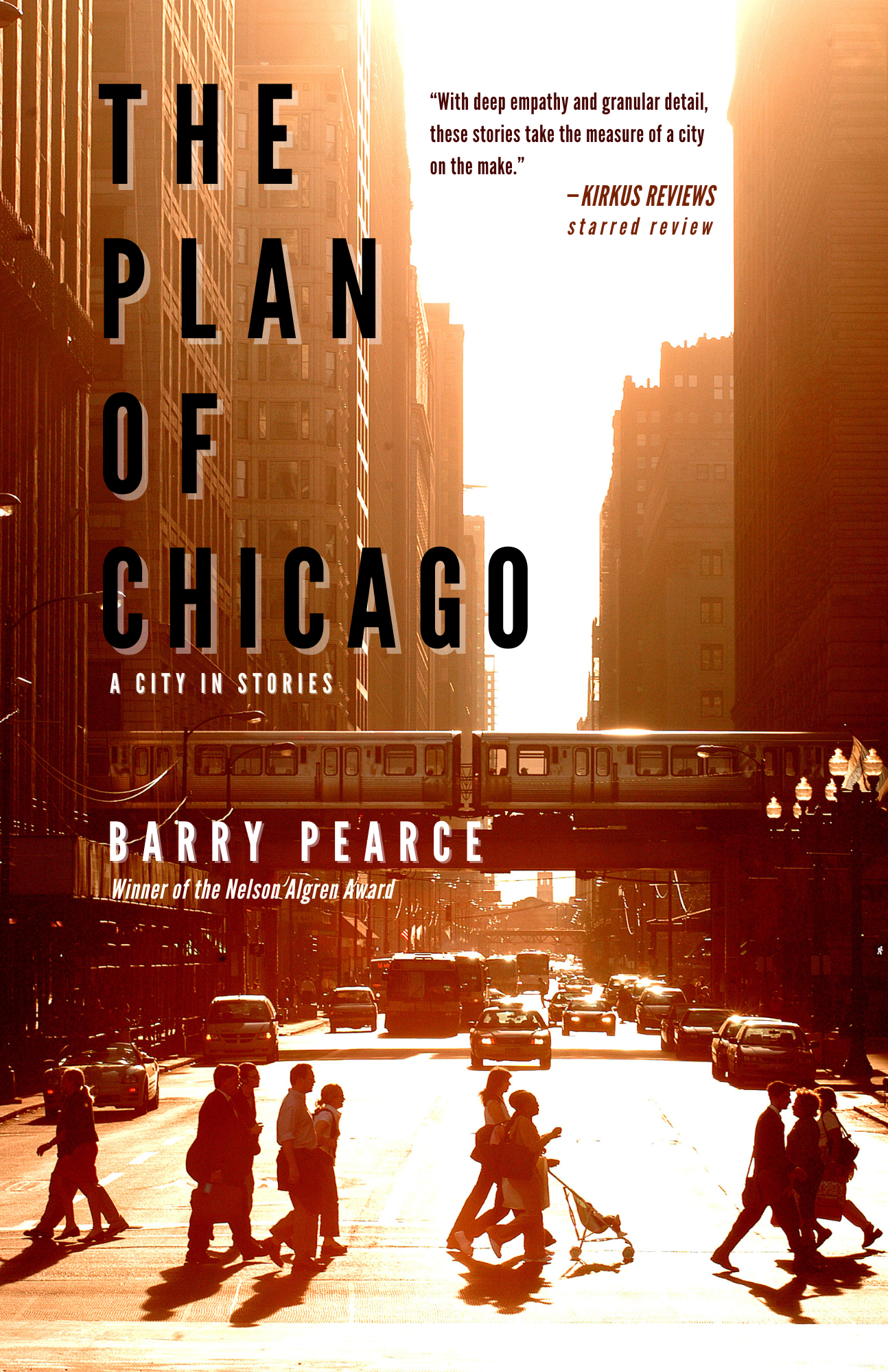

Chicago-based writer Barry Pearce is a worthy newcomer to their ranks. His debut collection, the vibrant, multifaceted The Plan of Chicago, features nine stories in which Pearce explores with insight and a sure hand the complexity and diversity of Carl Sandburg’s city of big shoulders. Along with Sandburg’s writing, The Plan of Chicago brings to mind Stuart Dybek’s searching, deeply sensitive, and often very funny short stories. Pearce is a writer who has an impressive range and an expansive heart. This is a terrific book." Christine Sneed talked with Barry Pearce about Chicago and the art of the short story for The National.

Q: “The Plan of Chicago” is a reference to a city planning document coauthored by Daniel Burnham. Did you start writing the stories in this book with that document in mind? Or did it come later? In your view, what is the plan of Chicago as you’ve interpreted it in these linked stories?

A: I did not have Burnham’s Plan in mind while I wrote these stories. The first full draft had a different title. The collection originally ended with a novella that included Daniel Burnham, Frank Lloyd Wright, and Louis Sullivan as characters, and “The Plan of Chicago” was mentioned explicitly there. When I finished “Enumerator,” the opening piece, the narrator, Margaret, kept talking about her plan to leave Poland and start a new life in Chicago. At that point, I realized I not only had bookends about “Chicago plans” but that all the stories in between seemed to involve people making plans that revolved around – and were often foiled by – the city.

The 1909 Burnham Plan was brilliant in some ways but also naïve and paternalistic – an attempt to impose order, homogeneity, and social control on a chaotic, wildly diverse place. I’m glad some brilliant bits were used – and that very little of it was realized. So, on one level, for me the title conjures the kind of idealized, almost Edenic vision that characters form around Chicago, only to see the city alter or shred their plans. The title and the epigraph from Burnham about a “City in a Garden” are ironic in this sense (as a reviewer at Kirkus wrote, not much here goes according to plan).

On a more literal level, the de facto plan of Chicago that evolved in place of Burnham’s scheme has many great elements but too often has relied on race, class, ethnicity, and violence as organizing principles. Dakhil, the Somali cab driver in “Lost and Found,” absorbs this “plan” as quickly as the official city grid: “He knew the official neighborhood boundaries, and the unofficial ones separating Black and White, Latin King and Vice Lord, posh and poor…”

The city makes space for beautiful collisions, like the moment of connection Dakhil feels with a rich white widow living in the Gold Coast, but systems stoking division are also, tragically, built into the plan of Chicago – biased policing, ethnic cronyism, a history of redlining, etc. At one point in “Lost and Found,” Dakhil sees a man selling rugs with animal designs outside a van on Division Street (a similar man sold similar rugs on that corner for years). The animals stare straight ahead as if trapped in woven cages, each wanting to escape but unaware of their neighbors’ similar desires. That image of compartmentalization, repeated in various ways throughout the book, sums up a key, unfortunate piece of the plan of Chicago for me.

Q: The first and longest story, “Enumerator,” features a Polish woman, Margaret, who has emigrated to the U.S. after she marries an American. She gets a job working for the census bureau. It’s a terrific story—full of humor, sadness, so many interesting characters and granular details about how to count people for the census. Did you do this work too? I also love the stories within this story. Were they there all along?

A: I’m so happy you like this story. It’s the last one I finished, and don’t we always want the most recent work to be our best? It’s also, I think, the strangest and most challenging piece in the book. It was definitely the most difficult to write – so many balls in the air. I did indeed work for the 2000 Census on NRFU, the Non-Response Follow-Up, counting people who hadn’t been counted because they never returned forms. I needed the money, but it’s one of the few times I went into something thinking of it as fodder for fiction. I paid attention and took notes, and I kept the handbook and forms and such, which was technically illegal (Shh!).

People have told me they read “Enumerator” as a story about someone gaining empathy. I think that’s true, though early on, I began to think of it as a story about someone becoming a writer (plenty of overlap there). Margaret, the narrator, moves from collecting the kind of basic info about people that fits neatly in boxes (more compartmentalization) to getting their real stories, counting them in a more substantial way. Fiction, at least for me, is all about counting the uncounted, and once I understood that metaphor, it seemed natural for Margaret to tell the stories of others within her story, which is about learning how to tell stories (sorry, so many stories!).

Q: You write from many different points of view, reflecting the multiplicity of the city and its inhabitants—young and old, Americans, immigrants, women, and men. How did you ensure that you were getting the voices and details right?

A: It’s a great question. First off, that was the project, to write a book about Chicago, as much of it as possible, which demands, as you say, reflecting the multiplicity of the city and its inhabitants. By some standards, no one is qualified to write such a book, but that means it never gets written, which would be too bad. It’s an incredible city whose diversity is its greatest strength and chief source of beauty. Should we not have a taste of that range on the page?

My answer is obvious, but it’s equally obvious that not everyone can write well about everything. My parents came here from Ireland, so I was on firm ground with the Irish characters. There are a lot of commonalities in immigrant experiences across groups, which gave me some insight into the many other immigrant characters, too. My neighborhood growing up was heavily Polish, with a growing Latino population, and it sat west of a huge, vibrant Black community.

So, one answer to your question is that of the hundreds of groups who might be represented, I leaned into those I had some experience with. Research played a role, whether that was hanging out in a neighborhood, talking to people, or reading books. Having friends with some authority vet various stories helped, too. At the end of the day, though, I think you have to go with what’s on the page and make a judgment call. Does it work? Does it pass what I’ve heard Dagoberto Gilb call “the scratch and sniff test.” I was fairly confident that the details and voice of the young gay African American woman in “Chez Whatever” seemed authentic. Despite our differences, I’ve never felt closer to a character. That is the most difficult and audacious thing, I think, to inhabit another human. If you get that right and you’re not completely out of your depth, the details will follow.

Q: You’ve published many of these stories in literary journals and won a prestigious Nelson Algren award for “Chez Whatever,” the story mentioned above. When you began writing them, did you see them as part of a book, organized by different Chicago neighborhoods (South Shore, Gold Coast, Bucktown, etc.) or did The Plan of Chicago come together over years?

A: The book evolved over many years. I didn’t start out with that structure – each story set in a distinct, labeled neighborhood, with characters overlapping. I was just working on stories, but over time, patterns and connections emerged. Once I saw them, the structure appeared organically. For instance, characters in “Enumerator,” “Chief O’Neill’s,” and “Clearing” were based on my brothers. I first tried to disguise them, but once I accepted the overlap between stories, it became an advantage, The characters deepened because I could explore them over longer periods and in different phases of life.

Once I started to think about how the stories worked together, I realized that each was set in a different Chicago neighborhood. Setting was not only important, it was generative. The place made or influenced the people, affected the plot, and provided imagery. Its dynamics were often the catalyst for the story. Giving setting that kind of role felt natural. I grew up in Chicago, obsessed with its neighborhoods, and as a journalist, wrote endless neighborhood profiles, which required sinking into communities – eating in the restaurants, walking the streets, catching music, drinking in taverns, and talking to residents. Chicago isn’t a town, really, it’s 200 towns, each with its own languages, character, culture, and politics. I find that fascinating, so it’s no surprise that this structure emerged.

Q: The concept of the American dream is an undercurrent that runs through all of these stories in one way or another. What other themes were you consciously (or unconsciously) exploring as you wrote this book?

A: I’m not religious in the least but as myth, the story of the Garden of Eden, with its themes of innocence, temptation, consciousness, and exile, gets referenced throughout the book. Characters often try to deny whatever new understanding they come to, scrambling for the biggest possible fig leaves. Sully in “Chief O’Neill’s” and Izzy in “Out of Egypt” deny knowledge they gain about their situations and those closest to them. Cynthia in “Swing Night” glimpses her tired, sordid relationship but insists that it’s special, and the unnamed narrator of “Chez Whatever” deludes herself into thinking she can undo her original sin if only she retells the story correctly. The fig leaves are already slipping, of course, and none of them will make it home again.

I didn’t understand how thoroughly the Edenic images and themes permeated the book until I was several full drafts in. That motif became an important through-line and on a larger scale, it echoes the Burnham Plan’s naïve utopian promise, that line about a city in a garden from the epigraph. On a still larger scale, beautiful, ugly, variegated Chicago, sitting more or less in the center of the country, is consciously a stand-in for America in the book.

The American dream, to return to your question, especially for immigrants, is another Eden story – innocence, vision of paradise, fall. Immigrants idealize the U.S. (or used to). They realize after arrival that the dream is, at least in part, nightmare, but exile is generally a permanent condition. They don’t quite fit here and can’t go back there, so like the character of Margaret in “Enumerator,” they “live in between.” That liminal space isn’t comfortable but it’s a great vantage from which to write.

Q: Do you have a favorite character or story? I’m showing my hand here – mine is the title story (aka “Enumerator”). Your main character is plucky and tough and beautifully complex.

A: I am thrilled once again to hear you like that story, but, Christine, no fair! It really is like asking who’s your favorite child. My cop-out answer is that different stories and characters have been my favorite at various times. “Chief O’Neill’s” is the oldest, and I think it’s the first story I wrote that felt competent, not that it was great, but that it worked. It was also the first piece of fiction I published, so it was the favorite for years.

“Chez Whatever” was a breakthrough of another sort. It won a prize and earned me actual cash (bringing my hourly rate up to $.02 an hour!), so it became the favorite. Now, as I contemplate a novel, “Enumerator” is in the running for me, too, partly because it’s the most novelistic piece in the book. It makes me feel that maybe I can get my teeth around this form that I find so intimidating.

Q: What are you working on now?

A: I am well into another collection of stories, these ones linked thematically, by architecture. I grew up accompanying my carpenter dad to jobs in downtown skyscrapers, which fascinated me. I later wrote about architecture as a journalist, and later still, became a docent at the Chicago Architecture Center, where I give tours. The novella I mentioned, with Burnham, Wright, and Sullivan as characters, appears in this collection. Every story has some connection to building or design, if not to an architect. I’ve learned as much about fiction from architects like Louis Sullivan as I have from writers, so the idea was a natural. With Sullivan’s dictum that form follows function in mind, I’ve felt both the freedom and need to experiment with the architecture of stories that are about architecture, which has been great fun.

I’m also working on a novel about a family of native Irish speakers who emigrate to the U.S. in the late ’50s. I’m reluctant to say much about it yet, but the oldest three boys are born there, three younger girls here, and the middle child, en route, as they travel by ship to New York. They come to see themselves as two families. The three oldest succumb to drugs and crime in their new home, the three youngest find success, at least on the surface, and the middle child escapes neighborhood blight only to be repeatedly dragged back. Yes, it makes The Plan of Chicago look like the lighthearted romantic comedy of the summer, but next, I will write something funny. Honest!

Christine Sneed is the author most recently of Please Be Advised: A Novel in Memos, and the story collections The Virginity of Famous Men: Stories and Direct Sunlight. She is the editor of the short fiction anthology Love in the Time of Time’s Up, and her work has been included in The Best American Short Stories, O. Henry Prize Stories, Ploughshares, New England Review, and numerous other publications. She has received the Grace Paley Prize in Short Fiction, the 21st Century Award from the Chicago Public Library Foundation, among other honors, and has been a finalist for the Los Angeles Times Book Prize. She lives in Pasadena, California and teaches creative writing for Northwestern University and Stanford University Continuing Studies.