Q&A: A Novel About Life in a Chicago Condo, and Dreams of a Better Path for Gaza

/In his newly published novel, Every Exit Brings You Home (W. W. Norton), Naeem Murr delivers a powerful exploration of a man navigating the fault lines between homeland and exile, conscience and survival, love and loss. Jamal “Jack” Shaban, a Palestinian immigrant from Gaza living in an ailing condominium building on Chicago’s north side, moves through his life as a caretaker: as a flight attendant tending to strangers in transit, a proxy superintendent managing the conflicts of his neighbors, and as a husband devoted to his wife, Dimra, whose fierce political clarity and physical suffering stand in stark contrast to Jack’s instinct for compartmentalization and secrecy.

Beneath his handsome and patient public face, Jack hides the pain of a history defined by violence and loss. Set primarily in 2007 and 2008 during a period of escalating violence in Gaza and the onset of the American housing collapse, Every Exit Brings You Home is deeply attuned to the meanings of home, exile, and return. Murr uses the intimate microcosm of a condo building—crowded with complex characters and daily frictions—as an analogue for much larger historical and political conflicts. The result is a work both personal and expansively geopolitical, animated by moral ambiguity, humor, and profound empathy.

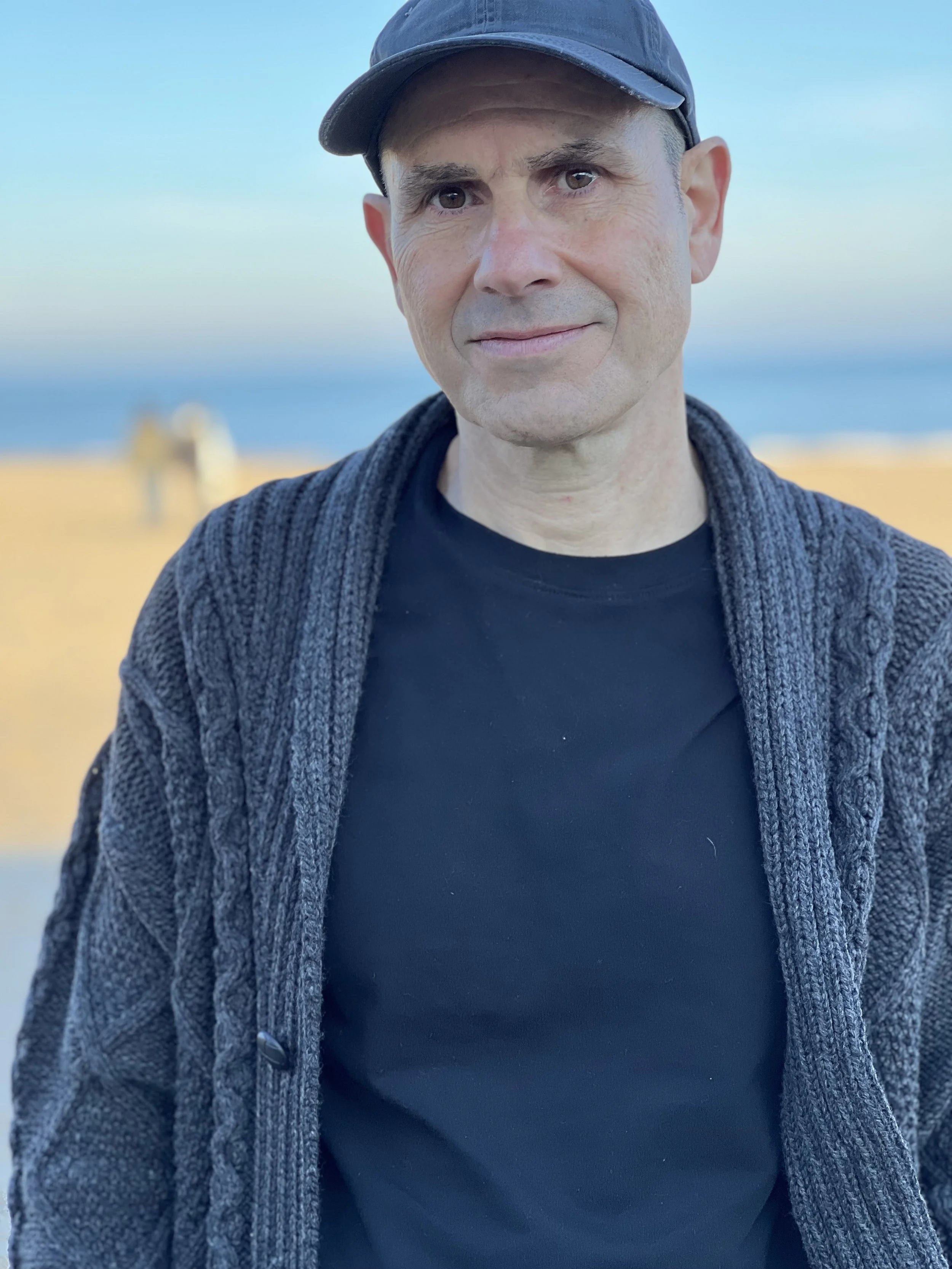

In this new novel and his three that preceded it, Murr explores mysteries lying behind ordinary façades, with characters shaped as much by silence and privacy as by their public-facing personas. What emerges in Every Exit Brings You Home is a vision of fiction not as explanation or argument, but as an act of attention—one that honors the unknowable core of human lives while insisting on their dignity. -- Christine Sneed discussed the themes and mysteries of Every Exit Brings You Home with Naeem Murr for The National Book Review.

Q. Jamal “Jack” Shaban is a generous, conflicted, wounded man whose past contains tragic and violent losses. He uncomplainingly and capably takes care of other people, as a flight attendant, as a husband to his wife Dimra who struggles with endometriosis, and as a proxy super to their neighbors in the ailing condo building, they inhabit in Rogers Park, a far northern Chicago neighborhood. How did he arrive in your imagination?

A. Every Exit Brings You Home was prompted nearly five years ago when I took a walk in my Chicago neighborhood one afternoon and noticed a man and woman sitting in an old Chevy Impala hitched to a U-Haul trailer just outside my condominium building. An infant sat asleep in the back. Though the couple were leaning tenderly against each other, they looked bereft—alone. I couldn’t tell if they’d arrived or were about to leave. It felt like the moment after the Biblical Fall.

My paternal family were Palestinian refugees in 1948, and for a while I’d been thinking about what “home” means for a Palestinian. Gaza was also on my mind because it had erupted into the worst violence in years over tensions in East Jerusalem. This prompted the idea for a novel about a Gazan immigrant to Chicago—Jack—the story catalyzed by a troubled and aggressive single mother moving into an apartment in his condominium.

This book felt as if it had been gestating in me for a long while and was ready to be written. It just needed the trigger of the couple in the Impala. When a book is ready in this way, the characters appear more or less fully formed, emerging and deepening as the story itself progresses. Indeed, they are the story. Before I began writing the novel, I had no idea what Jack’s history in Gaza had been or why he was forced to escape. I had no idea he’d be a flight attendant, or that he’d lead such a compartmentalized life, lying to everyone.

Only after I’d completed the novel and could look at it a little more objectively did I begin to understand why Jack behaves in the way he does, living these separated lives, this man with a past too full of love to cauterize, too full of pain to integrate. He’s a good man, but morally flawed and deeply aware of the capacity for evil in himself—in all of us. When I began the novel, I thought he’d be single, but Dimra, his wife, appeared. She’s a perfect contrast to him, Palestinian to the bone and obsessed with the Palestinian/Israeli conflict.

For Dimra, being Palestinian and Muslim is her identity, her essence, her being: I am what I am. For Jack, it’s his predicament: I am not what I am. But, again, I didn’t think about any of this beforehand. A novel always fails if a character is not substantial enough early on to challenge the author’s desire to control his fate and story.

Q. In an interview you did with your publisher recently, you said you write fiction because your Anglo-Irish mother told you nothing, i.e. she never talked about her past while you were growing up. Would you talk about this silence as a springboard to your becoming a novelist?

A. I grew up in London in the ’70s and ’80s. There were two silences in my home. One was rooted in my deceased Palestinian father, a black-and-white glamor shot of a man in his twenties on the mantle. This was a vast but impersonal silence. The other originated in my mother, a single parent working three jobs whose life in Ireland would have made Angela’s Ashes seem like a beach read. But she never said a word about her past. Her Irish brogue had been knocked out of her by the nuns at her convent school in Dublin, and she made sure that my brother and I spoke with an upper-middle-class accent far too posh for the working-class neighborhood we lived in. (At that time in England, the Irish were the lowest of the low).

All of this served to separate us as completely as possible from the suffering of her past, which also included her grief for my father. Childhood, of course, is the deep source of our creative selves, a time when the world has not been fully named, when we are at our most open and sensitive. In childhood, we know so little and intuit so much, intuitions that are not, at the time, articulated and therefore gather within them the primal force of mystery. From her silence, I intuited and absorbed the raw, generative substance of her tragic history. When I published my first novel, The Boy, I received a letter from my mother’s sister. She seemed to believe that the book had been based on her life. In fact, I’d had no idea my mother had a sister.

That deep connection with a loving but mysterious mother became part of a general fascination with the truth that lay behind every grown-up façade. Every adult became, for me, an aperture into their pasts, the stories of their lives. But there was also something unknowable in everyone, and that unknowable thing, their mystery, provided them with their dimension and dignity. For me, a significant character in fiction must maintain some level of mystery, of the unknowable within them. This is what brings them to life, allowing them to look back at me from the page. My fiction emerges out of mystery, silence, but the story isn’t an attempt to explain or solve that mystery, only to capture it in character.

Q. As alluded to above, Every Exit Brings You Home focuses on the complexities of identity, immigration, long-held secrets, and suppressed desires. Jack and his wife have emigrated from Gaza via Egypt to Chicago where they have lived for more than 15 years when the novel begins. What inspired you to set the story in a Chicago condo building?

A. At the most fundamental level, fiction thrives on conflict. I’ve lived in a condominium building for a couple of decades. In that time, I’ve witnessed and often mediated a great deal of conflict between the residents. The novel is set during the 2007/8 housing collapse, the condo on the verge of bankruptcy, putting even more pressure on its occupants. The building also has two tiers of property, with the above-ground units far superior to a badly built basement unit that deteriorates alarmingly through the course of the novel.

Rogers Park, where the book is set, and where I live, is also one of the most diverse neighborhoods in America, full of immigrants, many of them escaping persecution or conflict in their own countries. A condominium building is a perfect setting to explore all the complexities of the struggle of diverse people to share the same space, particularly when some of those people, like May [a Vietnamese immigrant], have been victimized in their pasts. In this way the building becomes an intimate analogy of the Palestinian/Israeli conflict, which is this same struggle writ large and in blood.

Q. To expand on the question above, when you begin writing a new novel or short story, do you think of setting before character or do they often coincide?

A. The setting is vital and intimately connected with character and predicament. Places, like people, hold stories, secrets. Every house is haunted. Setting is one of the means by which a story makes its meaning, generating elements of the story’s symbolic and idiomatic language. My previous novel, The Perfect Man, was inspired by setting. I was living in Columbia, Missouri, while my wife was finishing her Ph.D at Mizzou.

One day, walking in the eerie landscape of the Missouri floodplains, I came across a scattering of houses, clearly once a small community that had been rapidly abandoned, furniture, saucepans, children’s toys scattered throughout these derelict homes. Stumbling into this ruin full of ghosts within such an evocative landscape triggered my third novel, The Perfect Man, about five children coming of age in a small Missouri town, one of them an Anglo-Indian immigrant, Rajiv. Like my current novel, it seemed ready to be written, the characters leaping to life.

Only after it was finished did I realize that I’d finally written a novel I’d had in mind to write for decades about my childhood in a big block of flats full of working-class people in London in the ‘70s and ‘80s, as noted above. That place and time in London had transmuted into this small Missouri town in the ’50s and ’60s. Here was a childhood experience that had made the transition, as Rajiv had, as I had, into America, this town and place establishing a kind of Goldilocks distance from my own life, gifting me the creative freedom afforded by subverting my conscious mind.

In this way an actual story, freed from literal reality, can find its shape and integrity, a story that also incorporated my whole experience beyond childhood and up to that moment in Missouri, combining the sense of alienation I’d always felt in England with the experience of my later emigration to America.

With The Perfect Man, the setting came first, providing an experiential and historical particularity to characters who had been gestating in me for a long time in a more inchoate and archetypal form. Though Every Exit was inspired by the couple in the Impala, I knew that the condo setting was vital to the story right from the start.

Q. I loved your portrayal of Jack and Dimra’s distinctive neighbors, among them, May, the building whip; Gunther, who “borrows” artifacts from the Field Museum where he works; Marcia, a beleaguered mother of two whom Jack is very attracted to, in spite of himself. I know this is a work of fiction, but I’m wondering how your own experiences in a multi-unit dwelling might have influenced this novel.

A. Fiction is the drama created by people struggling to connect: to others, to that mystery that lies beyond (and within) the self. A condominium building is a perfect alembic for combining all those complexities of intimacy. You’re sharing a space with people who are often very different from yourself, people who aren’t necessarily friends, but with whom you have frequent contact and intimate knowledge.

A condominium can have thin walls. You hear people fighting, sobbing, making love. In this way you become part of a single body. Two people have died in my building. I watched one of them being turned slowly skeletal by chemo. I saw another stretchered dead to a waiting ambulance.

People go through relationship issues, divorces. At times, they tell you about this; at other times, you talk about the weather, avoiding the question of why their partner is gone. Living in a condo can be irritating, even infuriating, with neighbors who are loud, thoughtless, over-sensitive, even abusive. I’ve frequently fantasized about living in a house in the middle of the Alaskan wilderness! But the condominium is life, this struggle to work and find community with people unlike yourself: to drive a panicked neighbor’s child to the hospital, to search the neighborhood for someone’s dementia-addled parent, to organize a community garden.

Q. How did you choose the title, Every Exit Brings You Home? It’s haunting, lyrical, full of implicit longing, and I know it’s also not this novel’s first title.

A. The original title was Bye-Bye, Palestine, but my editor thought, and I agreed, that this might skew a potential reader’s approach to the novel, and didn’t really evoke the complexities of Jack’s predicament. Home is a complicated concept for any Palestinian, particularly one who grew up in a refugee camp inside the Occupied Territories.

Jack is also running from his past, and from himself. As a flight attendant, he could potentially fly anywhere he wants to. When he’s working, he’s constantly departing for distant locales, creating the illusion of escape. In the air, a plane is nowhere, a liminal space that suits him. But his final flight always returns him home. Returns him to Dimra, herself an embodiment of Palestine. The essential conflict within him—escape your past, you cannot escape your past; escape who you are, you cannot escape who you are—condemns Jack to be forever flying away from his home, forever returning.

Q. You deftly explain many of the factors leading to the decades of violent turmoil characterizing Gaza and Israel’s relationship. Their conflicts tragically remain as timely a topic as ever. Your novel is set in 2007 and 2008, but it feels as if you’re writing about present day. Had you already completed a draft of Every Exit Brings You Home when the events of October 7, 2023, took place? Tangentially, do you ever feel like fiction writers are clairvoyant?

A. I think much of the work of writing is subconscious, and I often think of the subconscious as a deep, connected root system like that of aspens. In this space resides not what we know but what we don’t know we know. My novel begins in 2007 with Hamas’s victory in the civil war resulting from their election and ends during what was then called “The Gaza War” in January 2009. This seemed a suitable period in which to end the novel because it was the worst outbreak of Israeli/Palestinian violence in Gaza to that point.

I began the novel in 2020 and finished the first good draft just a month or so before the October 7th attacks. It did feel to me as if my ending was a sort of backward echo of this horror, or—yes—a premonition of it. At the same time, this is the eternal present of the Palestinian/Israeli conflict, characterized since 1948 (and before) by this volcanic violence. These monstrous attacks and Israel’s brutal response were inevitable. This conflict is now rooted in the generational trauma of both Jews and Palestinians. Fear and hatred are destroying any capacity for imagination, and therefore for empathy. I have no idea how the small flame of imagination, of those with the capacity to conceive of peace and coexistence, can push back against the weight of that darkness.

Q. Despite the painful events that occur in Every Exit Brings You Home, there’s humor, too. Would you say your default mode is the comic—something John Updike once said about his own writing? Do you mindfully balance comedy and pathos in your work or is this blend more or less organic?

A. Horace Walpole described the world as a comedy to those that think, a tragedy to those that feel. While I hope I do think, I’m driven to write by a sympathy for the human condition—by feeling. I was born out of tragedy, my father’s death, my mother’s silence. My crucible was a block of flats full of broken families, abusive parents, addicts, old people barely able to live on the pittance of their pensions.

There are writers who are profoundly pessimistic. Just read Céline’s Journey to the End of the Night. Or the work of Flaubert, a man who wrote to George Sand, “I feel very old sometimes. I carry on and would not like to die before having emptied a few more buckets of shit on the heads of my fellow men.” But I’ve never felt hopeless or cynical and I’ve been blessed with a large capacity for love, joy, and happiness. This hope, this love, this capacity for joy is also a part of my work. I’ve never been interested in exposing or mocking humanity’s limitations, only in creating something that expresses—empathetically—humanity’s shared predicament. For me humor is part of the bittersweet weave of our lives. It allows for vital shifts in the music of narrative. It makes suffering bearable.

Christine Sneed is the author most recently of Please Be Advised: A Novel in Memos, and the story collections The Virginity of Famous Men: Stories and Direct Sunlight. She is the editor of the short fiction anthology Love in the Time of Time’s Up, and her work has been included in The Best American Short Stories, O. Henry Prize Stories, Ploughshares, New England Review, and numerous other publications. She has received the Grace Paley Prize in Short Fiction, the 21st Century Award from the Chicago Public Library Foundation, among other honors, and has been a finalist for the Los Angeles Times Book Prize. She lives in Pasadena, California and teaches creative writing for Northwestern University and Stanford University Continuing Studies.