REVIEW: When America's First Serial Killer Preyed on the Women of 19th Century Texas

/

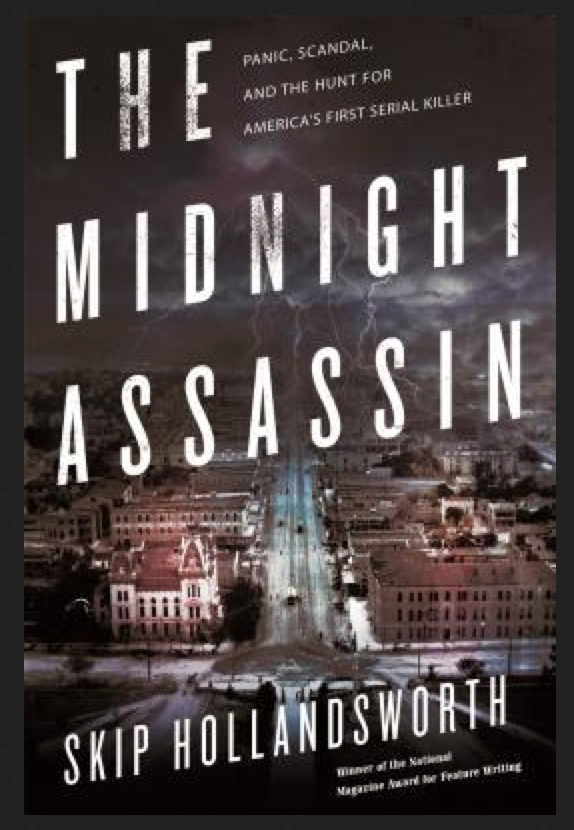

The Midnight Assassin: Panic, Scandal, and the Hunt for America’s First Serial Killer

By Skip Hollandsworth

Henry Holt 320 pp.

By Jim Swearingen

In the late hours of the night, a savage killer stalked a central Texas town. He preyed on young black servant girls, in the idiom of the day, terrorizing them by throwing rocks through their windows and breaking into their cabins surreptitiously, leaving their clothing and bed sheets askew. Then, dissatisfied with simply striking fear in helpless women, he turned to murder.

The year was 1885. The city was Austin. And for the panic-stricken citizens of Skip Hollandsworth’s The Midnight Assassin — for whom forensic science and the criminal psychological profile had not yet been invented — there was no rational explanation for the series of apparently motiveless homicides.

Over the course of a single year, an unknown serial killer carried out a spree of brutal murders targeting seemingly unrelated victims — a phenomenon as yet unheard of in American life. To the eye of a modern reader, who has likely seen countless forensic crime shows, the victims are not without their commonalities, and the attacks not without clues. Indeed, Hollandsworth takes pains to describe the repeated blundering of investigators who had only 19th century techniques at their disposal — enough to drive the modern mystery buff mad.

The crimes began as home invasions focused on tearing the bedding and apparel of young black servant women who dwelled in quarters behind their employers’ homes. With time, however, the prowler became bolder, as his fetish expanded into bloodthirsty physical assaults on the women themselves. The twisted libidinous rage of some of the attacks is shocking even by contemporary standards.

Honing his murderous craft, the psychopath began toying with local investigators, stealing a watch from one victim and placing it on the corpse of another, and laying firewood symmetrically across the body of a third. He always left a confused and terrified witness to the killing—often a traumatized child, who was unable to provide a definite description of the murderer.

A particularly sick and misogynistic aspect of his attacks was that they usually involved cleaving the victim’s head and face with an ax. On a couple of occasions, he essentially lobotomized his victim. And then after each attack, he disappeared. No Old West town marshal or posse-seasoned bloodhound was able to track the fiend down.

Hollandsworth skillfully blends a disturbing murder mystery with the history of the Lone Star State when it was just 40 years into statehood. The setting is an on-the-move Austin, just as it was shedding its small-town provincialism and hurtling into the 20th century. Austin's future as a big-state capital was symbolized by the capital building itself, which was still under construction, and designed to be larger than the one in Washington D.C.

The Midnight Assassin captures the lawlessness and ribaldry of frontier life—you can almost hear the tinny piano, the laughter, the squeals, the breaking glass and boot heels on wooden planks as a saloon fistfight spills into the street. At times the story reads like a Larry McMurtry western.

Progress was apparent on many fronts. Austin had just hired its first marshal who was not a gunslinger. The city council had allowed a black alderman to represent hia part of town. And a law to extend the vote to women was given a hearing, despite the winks and snickers that accompanied it. You could almost see modern America in the distance.

But Hollandsworth also, almost incidentally, dissects the anthropology of the twisted race relations that prevailed in postbellum America. That the first murder victims were black female domestics meant that these were low-priority crimes. Not until two white women were killed did the efforts of the townsfolk to deal with the butchery become serious—and destructive. Initially assuming that only a black man would be capable of such savagery, the police detained and questioned—and beat—multiple black male suspects. (One interrogation technique involved mimicking strangulation by noose, a 19th century version of waterboarding).

Only when some of the locals came to appreciate the intelligence and discretion of the killer did they consider that a white man might be the perpetrator. In a redirected form of racism, the previously unquestioned assumption that only a black man could be capable of such savage brutality gave way to the presumption that only a white man could be so cunning in his tactics.

The murder spree ceased as suddenly as it began, but the long-term effects on the city’s politics, civic improvements, and race relations went on for years. The frenzied investigations toppled political careers, prompted extravagant security measures, and banished black representation in city leadership for nearly a century.

Meanwhile, an infamous series of equally—though not identically—misogynistic attacks on female prostitutes was beginning in London. Jack the Ripper’s murders triggered speculation on both sides of the Atlantic that the Midnight Assassin might have relocated to England.

Ultimately, Hollandsworth’s efforts to identify the Austin killer and to link him to Jack the Ripper end where all previous attempts have ended—in inconclusive speculation. But along the way, he draws some strong parallels between the multiple layers of racial prejudice, suspicion, and paranoia in 19th century Texas and London authorities’ attitudes toward non-white and non-British “others” as they investigated their serial killer.

The Midnight Assassin would have benefited from even more mining of these rich lodes of racial politics and white paranoia, and a bit more intensive sociological analysis. Hollandsworth may have decided, however, that this was more than the average reader of a popular murder mystery had bargained for. Despite this modest deficit, Hollandsworth has delivered — for lovers of true crime stories, American history, and under-appreciated Texana — an irresistible spellbinder.

Jim Swearingen is a Minneapolis-based writer.